OPVET – Online Courses – DIVE

OPVET VOOC

Introduction to the VOOC

The purpose of the OPVET Vocational Optional Open Online Course (VOOC) is to introduce future and current vocational teachers to new ways of integrating digital technology, media, storytelling, and intercultural communication for teaching and learning in vocational teaching.

The VOOC consists of three modules:

- English and Digital Storytelling

- Inter-cultural Communication

- Digital Media in Teaching and Learning

The modules consist of texts, videos, reflection tasks, assignments, and links to various resources that are relevant for the different topics. The in-text citations and list of references are formatted using the APA7 referencing style. You can learn more about this referencing convention from Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL).

Instructors and developers

The course instructors that you will meet in the VOOC are Petri Salo (Åbo Akademi University), and Johanna Björkell (Åbo Akademi University). In addition, Fredrik Mørk Røkenes (NTNU) has developed content in the VOOC while Britt Karin Støen Utvær (NTNU) has coordinated and leaded the project together with Agneta Knutaas (NTNU).

About OPVET

The OPVET project has the primary goal of supporting organizations in higher education. The aim is also to develop and reinforce (international) networks with upper secondary education, to increase the capacity and operate at a transnational level to internationalize the education and training of students in vocational teacher education (VET). Read more about the project results on OPVET.eu, and get in touch with us to learn more.

Reflection vs Description

Reflection vs Description

The concept of "reflection" or "to reflect upon" something can be understood as the action of "thinking deeply or carefully about" an issue (Lexico: English and Spanish Dictionary, Thesaurus, and Spanish to English Translator). Reflection is something we do not explicitly think about, but that we do on a daily basis; should I get a new pair of jeans? will they look good on me? can I afford them or should I go for the cheaper pair? In contrast, the term "describe" or "to describe" something can be understood as to "give an account in words of (someone or something), including all the relevant characteristics, qualities, or events" (Lexico: English and Spanish Dictionary, Thesaurus, and Spanish to English Translator).

In education, having students reflect rather than just describe is encouraged as a way to develop so-called lifelong learning skills, promote critical thinking and metacognition, meaning an "awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes" (Lexico: English and Spanish Dictionary, Thesaurus, and Spanish to English Translator). However, reflection is not only reserved for students and is also a regular practice among teachers; what are the learning aims for the next lesson? how can I ensure that my students meet these aims? how will I assess my students and how can they provide evidence that they have met aims?

In some of the tasks in this VOOC, you are asked to reflect on your teaching experiences from vocational education with (or without) the use of digital technologies and media. The goal is to encourage you to ask your own students to reflect on their learning experiences from their vocational practice period or workplace apprenticeship, and to show you how digital technologies and methods (such as digital storytelling) can be used as a tool for teaching, learning, and reflection. Being aware of when you are describing and when you are reflecting is important to keep in mind when approaching the tasks in the VOOC.

According to the philosopher Donald Schön, reflection can be understood as either "reflection-in-action" versus "reflection-on-action" (Schön, 1983). You can read more about these concepts online. However, the take-away message is that professionals (skilled workers, lawyers, doctors, researchers, and so on) constantly have to reflect on what they are doing as they are performing an action (reflection-in-action) and why they are doing what they are doing (reflection-on-action).

Module 1: Digital Storytelling

Introduction to Digital Storytelling

Introduction to Digital Storytelling

Introduction

Welcome to this module on English and Digital Storytelling! The purpose of the module is twofold; 1) to introduce how vocational education teachers (VET) can implicitly work with students' English language learning skills while explicitly focusing on creating and reflecting with digital storytelling, and 2) practicing what the philosopher Donald Schön refers to as "reflection-in-action" versus "reflection-on-action" (Schön, 1983).

The module is primarily focused on English and second/foreign language teaching (ESL/EFL) and vocational educational teaching, and linked to relevant competence aims which can be expressed in various concrete learning aims and activities. However, the Digital Storytelling method can also be applied to other subject disciplines at different levels of education and is quite popular for working with history, social science, arts and crafts, and special education.

Before you start working with the module, it might wise to revise some of the reading materials listed below, starting with the article listed first and then moving down the list to the bottom. The reading material is meant to clarify and expand upon theoretical and practical concepts related to digital storytelling, and inspire you to think about how you can integrate the digital storytelling method in your own teaching.

Reading materials for this lesson

Kajder, S. B., Bull, G., & Albaugh, S. (2005). Constructing Digital Stories. Learning & Leading with Technology, 32(5), 40-42.

Ohler, J. B. (2013). Defining and discussing digital storytelling. In J. B. Ohler (Ed.), Digital Storytelling in the classroom (2 ed., pp. 23-44). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Røkenes, F. M. (2016). Digital storytelling in teacher education: A meaningful way of integrating ICT in ESL teaching. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(2), 311-328.

What is Digital Storytelling?

What is Digital Storytelling?

Digital Storytelling is the art of combining a narrative (in the form of a written script which is recorded) with various digital media, normally in the form of pictures and sound (but it could also be with video clips). The use of digital storytelling as a method and for different purposes can be observed in several disciplines such as a research method (De Jager, Fogarty, Tewson, Lenette, & Boydell, 2017), health work (Jamissen & Skou, 2010), settlement (Lenette, Brough, Schweitzer, Correa-Velez, Murray, & Vromans, 2019), and community leadership (Brushwood Rose, 2019). In education, digital storytelling can engage pupils in both traditional and new ways of telling stories and has also proven to be a positive and constructive way for struggling pupils to "tell" and “write” stories (Lambert, 2018; Miller, 2014; Ohler, 2013; Wu & Chen, 2020). Digital storytelling has also proven to be a way of developing professional digital competence (PDC) in future and current teachers who in turn must stand out as a good digitally competent role model for their pupils (Røkenes, 2016). The video below sums up the main elements in digital storytelling.

A digital story is normally 2-3 minutes long where the narrator deals with/reflects on a critical incident and is usually based on a written script of around 150 – 300 words (Røkenes, 2016). The number of pictures needed depends on the rhythm and the pacing of the story, but between 6-12 pictures should be enough. However, depending on the purpose of the story (to describe and/or to reflect on an incident, experience, story, artifact, and so on), the digital story can vary in length and number of pictures. Moreover, digital storytelling differs from a randomly composed slideshow with music and photos in the sense that a digital story is often linked to a task with specific requirements such as focus, choice of theme, and assessment (Normann, 2012a).

In a well-composed digital story, all elements must be carefully chosen, with respect to if and how they should be part of the story. This means that the producer of a digital story should not focus on using the various digital media simply as a form of decoration or “wrapping” of the story presented. Instead, he or she should always question (or reflect upon) whether pictures, sound, animations, transitions, and the editing (i.e. choice of font, color, and animations) of the text slides used (i.e. slides mainly used in the beginning and at the end of a digital story) support, emphasize, expand or contrast the overall message of the story. Consequently, introducing the digital storytelling method in a classroom might take up a significant amount of time, and is usually organized as a long-lasting project, workshop, part of a summer school or an after-school enrichment program (Wu & Chen, 2020).

Joe Lambert (2018) at the Center for Digital Storytelling in California has come up with seven steps or elements to think about in order to create a personal narrative in the form of a digital story. During the writing process, he tells us to think about the following aspects: 1) point of view; 2) a dramatic question; 3) emotional content, and 4) economy. During the creation/editing process, we should consider the importance of 5) pacing, 6) the gift of our voice and 7) a soundtrack. For more information, check out the website hosted by The University of Houston, TX.

Relevant software for story telling

Relevant software for story telling

Software for recording and editing digital stories

There are various video editing and recording tools (software) that can be used when making digital stories (Ohler, 2013). The most common ones are:

- Adobe Spark (runs in web-browser, free)

- Microsoft Sway (Windows, MAC OSX, free, requires Microsoft Office 365)

- OpenShot video editor (Windows, MAC OSX, Linux, free/open-source)

- Shotcut (Windows, MAC OSX, Linux, free/open-source)

- Screencast-O-Matic (Windows, MAC OSX, free, can also run in web-browser)

- iMovie (MAC OSX, preinstalled on MAC)

- Microsoft Teams/Stream (Windows, MAC OSX, requires Microsoft Office 365)

You might ask yourself; what tool should I use? There are just so many to choose from! Most of the tools listed above have a similar structure, logic, and interface. However, Adobe Sway is highly recommended because it can be run directly through your web browser and it does not require you or your students to download and install any software on your local device. Another alternative is creating a slide show with photos for your digital story in for example PowerPoint and then recording the video with narration using Screencast-O-Matic.

Most students today are familiar with video editing and video recording tools on their mobile devices (smartphones, tablets, laptops). However, this might not always be the case with teachers. Therefore, when installing or running one of the tools mentioned above, a good place to start looking for guides, tutorials, and demonstration videos is YouTube. In the search field on YouTube, try searching for the name of the program and guide or tutorial or demonstration (for instance, how to use Adobe Spark Video or Screencast-O-Matic tutorial).

Alternatives to Digital Storytelling

Alternatives to Digital Storytelling

Storybird

Yet another way of creating digital stories is through the freely available web application Storybird where the focus is on telling stories through text and pictures. Teachers and pupils can access Storybird through their web browser and can choose to create three types of stories: 1) Longform Book, 2) Picture Book, and 3) Poem. In Storybird, pupils do not have to spend time on finding images and on recording their own voice, as in digital storytelling created by using video editing software. All they do in the web application is to choose a set of artistic, themed images that they would like to use for their text (a selection of sets of artistic images are available) and then add text, which can be either a Longform Book with several chapters, a Picture Book or a Poem. They can additionally choose whether they would like to invite peers to collaborate on their story and also whether they want to share it in public or keep it private.

In addition, Storybird (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. is an application that allows pupils to use technology and work collaboratively. Moreover, using this application does not require much preparation time from the teacher, apart from creating a class account. As you will discover when you access the website and register a teacher account, this application is a great way to get pupils reading stories others have made and published, and also an excellent tool for writing their own stories, in a chosen genre. Note also that teachers can create class accounts, allowing one account to be used by up to 30 pupils.

Here is a Prezi presentation about how Storybird can be used in the Classroom. Stories created in Storybird are interactive and resemble a dynamic text rather than a playable video similar to those associated with the digital storytelling method. However, if a pupil were to record themselves reading and reflecting on their Storybird story using screencasting software such as Screencast-O-Matic, they can create playable videos with overlying narration (and also open up for the potential use of music and other types of audio-visual effects).

Finally, digital stories are also popular among authors, journalists, and organizations who are trying to come up with new ways of making their materials interesting by making use of the affordances that are presented in the digital medium versus on paper. For example, take a look at the digital stories "The Boat" produced by SBS and The Martian Diaries by Science News. In these so-called multimodal texts (Bezemer & Kress, 2016), several modes of representation are combined to create dynamic stories where the reader can interact in different ways with the "text" and is presented with multiple layers of meaning through pictures, animations, sounds, videos, and text.

Educational purposes of digital story telling

Educational purposes of digital story telling

Language learning and digital storytelling

Working with digital storytelling in an ESL/EFL or any other language class for that matter, in vocational studies or other subject disciplines can easily be aligned with several competence aims/goals in your national curriculum and can be expressed in the form of various, specific learning objectives/outcomes. Digital storytelling is a method or working process that lends itself easily to combining the development of language skills as outlined in the Common European Framework of References for Languages including reading, writing, listening oral production and oral interaction (Council of Europe, 2018) and basic skills as outlined in the Norwegian National Curriculum for Knowledge Promotion including reading, writing, oral skills, numeracy, and digital skills (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020). On the one hand, students can work with specific content areas (e.g. literature, items and tools, work practice placement) and on the other hand practice various skills (language and basic).

Below are examples of digital stories created by students, pre-service teachers, and former vocational education student teachers taking this VOOC. A common feature that you might notice in several of the examples is that there is an emphasis by the narrators on description and describing events/artifacts rather than reflection and reflecting on how these events/artifacts play a role in one's education or affect how you are feeling. Again, digital stories are supposed to primarily focus on the narrator's reflection tied to the focus of the story and so keep this in mind when developing your own stories.

Literature and digital storytelling

When working with literature, digital storytelling can be used by the teacher, either as a way of introducing a literary text or as a way to spur the pupils’ interest and curiosity for the text to be studied. The most exciting way of using it, however, is to allow pupils to be creative and develop their own digital stories related to the text studied. This can e.g. be in the form of a personal, digital story, like in the example, I Love Matilda, made by an 8th grader some years ago. The girl, Julie, did not want to talk English out loud in class, but gradually got to practice her orals skills through making DSTs to the point where she was able to hold a presentation in English in front of the class (Normann, 2012b). The task here was to make a digital story related to a good book the pupils had been reading themselves, or a book that had been read aloud to them by their parents.

Another digital storytelling task related to reading literature was done in a web-based further education course on "Literature and Culture in the Classroom" for English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers in the Norwegian secondary school. The group of teachers were working with different young adult fiction novels such as John Boyne’s (2006) famous novel The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. After having studied and worked on the novel for some weeks the teachers were asked to finalize the project by making a digital story. The specific task was to EITHER choose one of the characters in the novel and to present a story as this character could have told it OR tell a story from one's own perspective about the reading experience with a focus on the emotional/aesthetic dimension. The story had to be based on something that actually took place in the book so that the peers in the course could recognize the story when they watched the actual interpretation in the form of a digital story.

Vocational education and digital storytelling

For vocational studies, digital storytelling is a highly relevant way of showing knowledge about a specific content area such as tools, working methods, and telling stories about relevant experiences during the work placement as a part of the apprenticeship.

Here are examples of digital stories created by former VOOC participants. The first example is from a Child and Youth Worker. Pay attention to how the participant manages to strike an impact (skape et anslag) on the viewer within the first 30 seconds of the digital story.

The next example is from a participant who reflects on his observations from his work placement at a lower-secondary school. The video consists of sections that have been cropped together.

Finally, the last example is from a participant who, towards the end of his digital story reflects on negative and positive aspects related to the future of the workplace in times of Corona.

The digital story telling process

The digital story telling process

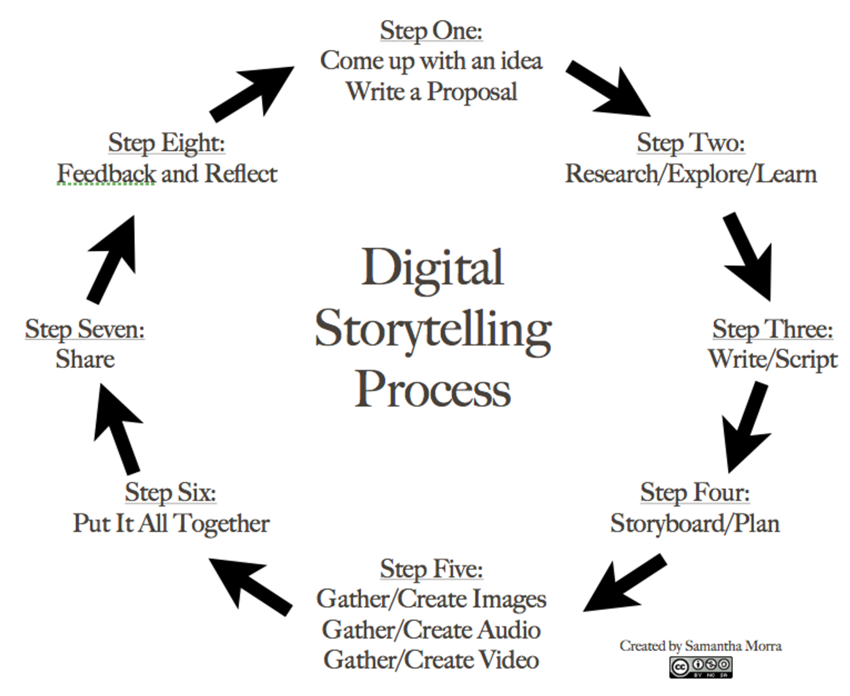

As illustrated in the image below, the work process with digital storytelling usually involves eight steps:

- Coming up with an idea or "finding the story"

- Researching and exploring the topic of the idea

- Creating a manuscript or "writing the story"

- Planning the story using a storyboard or a timeline

- Searching for and gathering relevant photos, images, illustrations, videos, music, sounds including recording the narration

- Composing the different elements of the story in a video editing software

- Exporting, publishing and sharing the story on a video platform (YouTube, Vimeo), a local platform or LMS (learning management system)

- Assessing and providing feedback on the digital stories

1. Coming up with an idea or "finding the story"

In order to "find the story", pupils will usually have to work on a subject-specific task that is provided by the teacher (for example, make a story about an important event during your apprenticeship/work placement). Having pupils practice free-writing (write non-stop about a topic for one minute) or use mind mapping tools (e.g. Mindmeister, Coogle) can be relevant to generate ideas.

2. Researching and exploring the topic of the idea

Once the pupils have come up with an idea for their stories, they should test their ideas by discussing them with their peers and the teacher. First, pupils could work in pair, then in groups of four and finally, the teacher could ask the groups to share their ideas in plenary or write their ideas down on a large piece of paper that is hung up in the classroom or on a digital board (e.g. Padlet, Flinga).

3. Creating a manuscript or "writing the story"

After having their ideas for their stories tested and approved, the pupils should focus on writing a first draft of the manuscript to the story. Here, the teacher can set limits on how many words the text should be depending on the level of the pupils and also open up for differentiation. Drafts could be shared and commented on by peers and/or the teacher where the pupils revise their texts and create new drafts.

4. Planning the story using a storyboard or a timeline

At the next stage, pupils will usually be busy trying to find images that fit with their stories. However, pupils have a tendency to focus on superficial aspects of their stories and waste a lot of time trying to find the "right" pictures. Therefore, a useful non-digital tool for working with the manuscript and the content of the story is to use a storyboard ("Dreiebok" is a more commonly used term in Norwegian).

Students have to plan their stories by filling in the matrices on paper (before working with their computers or mobile devices). That way, they get a clearer perspective of what their stories are about, who is involved, how their stories are built up, how they progress and what are the main points or messages of their stories.

5. Searching for and gathering relevant photos, images, illustrations, videos, music, sounds including recording the narration

Pupils usually master the stage of finding photos, music, and recording narration either using their laptops or mobile devices. However, having the pupils find pictures that fit their stories opens up for the teacher to differentiate and create interesting topics of discussion; Can photos and music be downloaded freely from a Google search? What about copyright? Where can media be downloaded freely? How does Creative Commons work? Here, the teacher can provide the pupils with media resources where they can find freely available images, photos, and music such as Pixabay, Unsplash, and Premium beat.

6. Composing the different elements of the story in a video editing software

When putting the digital story together, pupils should try to use software that they are comfortable with and available to them such as the ones listed on the suggested software page of this VOOC. Usually, there will be a technical expert in the classroom who can provide assistance to their peers or the teacher can direct the pupils to online tutorials on for example YouTube or Vimeo.

7. Exporting, publishing and sharing the story on a video platform (YouTube, Vimeo), a local platform or LMS (learning management system)

Once the pupils are finished their digital stories, finding a place where the stories can be shared will be important. Here, the teacher needs to take into account that not all pupils will feel comfortable with sharing their stories and so should open up for alternatives (closed submission folder on local LMS vs unlisted video link on YouTube/Vimeo).

Assessment and Digital Storytelling

Assessment and Digital Storytelling

Assessing and providing feedback on the digital stories

Digital storytelling works well with both formative and summative assessment. For instance, pupils can get feedback during the work process on their digital stories (formative) and on the finished digital product (summative). At the end of a digital storytelling project, it can be motivating for the pupils to arrange a "film festival" or an "Oscar's" where the teacher shows all of the students' digital stories in class, where there is popcorn and sodas, and where everybody dress up to celebrate the end of the project.

Additionally, digital storytelling can be used as a part of a portfolio assessment where pupils get to produce several digital stories during their education and then document their own progress and development over time. Teachers will then have a concrete digital product where they can assess a range of competencies such as content knowledge, skills, reflections, and creativity.

However, assessing digital stories is often perceived as challenging by teachers who are not trained to give feedback on videos/multimodal compositions (Aagaard, 2014). Therefore, it can be wise to ask pupils to also write a short reflection text after they are done with their digital stories. In these texts, the teacher can ask the pupils to reflect on the work process (How was it working with digital storytelling?), the finished product (Are you satisfied with your story? What would you have done differently?), and their subject learning (What did you learn in the subject from working with digital storytelling?). Finally, both the digital story and the reflection text can be assessed from a language point of view in terms of pronunciation, flow, grammar, and vocabulary.

A useful tool for assessing digital stories is using rubrics such as the one below. Here, teachers can use these rubrics to give both formative and summative assessments to their students (by marking the descriptor that fits best with an "X"). Moreover, these rubrics do not always need to be filled out by the teacher, but can also be filled out by the pupils themselves in form of peer-assessment (pupils assess each others' digital stories and reflection texts) and self-assessment (students assess their own digital stories and reflection texts). There should also be an option to write more detailed feedback in the rubrics so that the teacher or peers can clarify. When developing rubrics, it can be wise to also involve the pupils so that they also take ownership of the assessment criteria for the digital storytelling project.

Further reading and references

Further reading and references

Further reading

Lambert, J. (2018). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community (5 ed.). Routledge.

Ohler, J. B. (2013). Digital storytelling in the classroom: New media pathways to literacy, learning, and creativity (2 ed.). Corwin Press.

University of Wollongong Australia (n.d.). Digital storytelling.

References

Aagaard, T. (2014). Teachers’ approaches to digital stories: Tensions between new genres and established assessment criteria. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(3), 194-215.

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2016). Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame. Routledge.

Boyne, J. (2006). The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. David Fickling Books.

Brushwood Rose, C. (2019). Resistance as method: unhappiness, group feeling, and the limits of participation in a digital storytelling workshop. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1-15.

Council of Europe. (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Companion volume with new descriptors. Council of Europe Publishing.

de Jager, A., Fogarty, A., Tewson, A., Lenette, C., & Boydell, K. M. (2017). Digital storytelling in research: A systematic review. The Qualitative Report, 22(10), 2548-2582.

Jamissen, G., & Skou, G. (2010). Poetic reflection through digital storytelling – a methodology to foster professional health worker identity in students. Seminar.net - International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 6(2), 1-15.

Kajder, S. B., Bull, G., & Albaugh, S. (2005). Constructing Digital Stories. Learning & Leading with Technology, 32(5), 40-42.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

Lambert, J. (2018). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community (5 ed.). Routledge.

Lenette, C., Brough, M., Schweitzer, R. D., Correa-Velez, I., Murray, K., & Vromans, L. (2019). ‘Better than a pill’: digital storytelling as a narrative process for refugee women. Media Practice and Education, 20(1), 67-86.

Miller, C. H. (2014). Digital storytelling: A creator's guide to interactive entertainment (3 ed.). Focal Press.

Normann, A. (2012a). Digital storytelling i engelskfaget.

Normann, A. (2012b). ”Det var en gang ei jente som ikke ville snakke engelsk – bruken av digital storytelling i språkopplæringa”. In H. K. Haug, G. Jamissen, C. Ohlman (Eds.). Digitalt fortalte historier (pp. 185-197). Cappelen Damm.

Ohler, J. B. (2013). Digital storytelling in the classroom: New media pathways to literacy, learning, and creativity (2 ed.). Corwin Press.

Røkenes, F. M. (2016). Digital storytelling in teacher education: A meaningful way of integrating ICT in ESL teaching. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(2), 311-328.

Wu, J., & Chen, D.-T. V. (2020). A systematic review of educational digital storytelling. Computers & Education, 147, 103786.

Module 2: Inter-Cultural Communication

Introduction to Intercultural Communication

Introduction to Intercultural Communication

Welcome to the second Vocational Optional Online Module of the OPVET Project!

After the introductory module on Digital Storytelling, we will explore another interesting topic, Intercultural Communication.

Intercultural communication in reference to education cannot be just a simple ‘add on’ to the regular curriculum. It needs to concern the learning environment as a whole. It also involves educational processes, such as school life and decision making, teacher education and training, curricula, languages of instruction, teaching methods and student interactions, and learning materials. The increase in knowledge (on the topic of intercultural learning) comes on an individual level, from experiencing other ways of doing and being. Experiencing that which is ‘other’ influences our emotions and our behavior and it enhances an increased repertoire when interacting with members of multiple cultures, both abroad and at home.

As the first step in this learning path in getting to know the important subject of Intercultural communication, familiarize yourself with this article about intercultural learning. The article describes perfectly the theoretical and conceptual framework of an understanding of intercultural learning.

Reading material for this lesson

Otten, M. (2003). Intercultural learning and diversity in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 7(1), 12-26.

Defining Culture

Defining Culture

Defining culture is a complex task. First of all, cultures can be seen as societal norms. Consequently, cultures are described in terms of the practices and values that characterise them, supporting directly or indirectly some modes of speaking and behaving, according to what is perceived as a particular valued way. Within this view, cultural knowledge is acquired by learning what people from a specific cultural group are expecting from us, as visitors to that culture, and adopting it as an appropriate way of behaving and interacting in the community.

However, this perspective has been criticised, as it is based on the assumption that cultures are a relatively static and homogeneous whole. In turn, this entails the risk of building cultural stereotypes, i.e. generalising some conceptions about the culture, often based on vague (or even negative) assumptions.

Cultures can also be regarded as symbolic systems that allow members to construct meaning through everyday practices developed in specific contexts. From this view, cultures are conceived as a system of shared meanings that help participants make collective sense of their experience through social communication. Symbols are part of the process of making meaning, enabling interpretation through extended participation in community life.

In this respect, learning is the fundamental way in which people, as participants in cultural communities, develop the interpretive resources they need to understand everyday activities and consequently, to be accepted as members of that community. Instead of assuming that the individual is an isolated entity equipped with essential and general features that might be more or less influenced by culture (generally thought of as a static collection of characteristics of the external environment), human development is seen as a process in which, through ongoing participation in shared activities, people contribute to fulfil changes in their communities across generations.

An introductory video on culture

PELLEGRINO RICCARDI talks about CULTURE.

Cultures can be also understood as practices. The perspective of culture as practices sees this as a dialogic activity, through which individuals achieve a discursive articulation of embodied actions that they fulfil in a specific space and time. Consequently, cultures can be seen as an emergent and dynamic interaction developed by community members who not only share coherent frameworks about experience, but also continuously reshape and negotiate meanings as they face the challenges of everyday life. Through this situated process, people try to construct a viable line of action from the existing resources offered by their culture. As a result, the cultures-as-practices paradigm considers individuals as being able to participate in different social groups and simultaneously develop their actions in multiple cultural environments.

It is also important to point out that becoming aware of the social norms and cultural values associated with the specific situation at stake during conversations is essential to effective communication with others in a second language. Therefore, the development of second language teaching strategies is based on dynamic approaches, involving techniques such as the use of authentic materials and role play. It is also suggested that teachers tend to value and encourage communication that is closely related to local culture. Consequently, the communication patterns of students from different cultural backgrounds are often regarded as inappropriate or defective. By delving more into the linguistic and cultural features of the second language, teachers can significantly increase their ability to provide students with meaningful learning experiences.

Finally, more specific topics related to culture and intercultural communication could be developed, such as the role of gender, religious observance and prohibition, or family life. All these topics, which cannot be fully explored here, are really important in educational contexts. Indeed, pre-service teachers will, in their future careers, most likely encounter students from a range of cultural backgrounds in their classes.

Video: Introduction to Intercultural Education

Additional resources:

If you liked the Pellegrino talk on culture here is a longer version: Cross cultural communication | Pellegrino Riccardi | TEDxBergen.

Exercises in Intercultural thinking.

It is suggested that students, after watching the video, reflect on the following questions:

- How should we approach ‘the other’, those who we perceive as being different from us?

- How can we foster a climate of dialogue and mutual encounter within the school and in classrooms, between students and between students and teachers?

- How can we create a culture of encounter, between ourselves and others?

- What are the possibilities for mutual enrichment between cultures and traditions?

Reading material for this lesson:

Gutiérrez, K. D., & Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational researcher, 32(5), 19-25.

What is Intercultural Communication?

What is Intercultural Communication?

The relationship between intercultural communication and education has been investigated since the 1960s, by observing how language acquisition and the development of knowledge are influenced by classroom communication. The study of intercultural communication is based on the assumption that all human interaction is, in part, a cultural expression. Our cultural identity and meanings are created through mutual interpersonal communication. Accordingly, analyzing intercultural communication enables us to become more aware of our assumptions about cultural values and accepted behavior, which are influenced both at the cultural and the personal level.

The development of intercultural communication as a research and educational topic has helped to disseminate the concept of culture as a notion that interconnects and overlaps with many social categories like race, ethnicity, social class, age, generation, gender, sexual orientation, disability and, more generally, diversity. Most categories usually work in combination in each individual, shaping what can be defined as his/her cultural identity.

More precisely, “intercultural communication” denotes the interaction emerging when people take part in verbal and non-verbal exchanges with others whose assumptions, sense making, behaviors, and experiences are different. Even though this interaction is commonly based on material culture, that is to say literature, art, architecture, food, and histories, intercultural communication cannot be reduced to those objective references. Moreover, human communication cannot be considered as a kind of neutral activity or substrate to which cultural factors are added. Rather, intercultural communication should be seen as a process of mutual engagement aimed at co-creating shared meanings, which are consistently affected by cultural assumptions, behaviors, and expectations.

Video: Intercultural Communication.

As a part of our subjective culture, these elements are so deeply embedded, through formal and informal learning, so that they are easily conceived as “natural”. This frequently leads subjects living within a specific cultural framework to conceive of their assumptions, behaviors, and expectations as undisputed matters, which are based on common sense and have simply to be taken for granted. Consequently, communication is intercultural not because of its content, such as exotic food, or its medium, such as foreign languages, but because it is a process through which our intrinsic beliefs are questioned and our certainties on the “right way” of doing things are challenged. Even though it is frequently expressed at the interpersonal level, many intercultural encounters also concern systemic histories and practices. These are important features of intercultural communication, particularly in relation to power relationships and intergroup dynamics.

Reflecting on this process helps us to understand the cultural patterns that are created by generalizing what we learn from, and share with, others inside a large or small community. As a research and educational subject, intercultural communication delves into the ways in which similar points of tension and conflict arise in communication, irrespective of the specific cultural background involved.

As for school, teacher questioning is especially important, as it is the most common way to prompt reactions from students and encourage them to actively participate in learning interactions. However, culture deeply shapes this process, depending on the attitudes of students and teachers towards the context. In many cultural contexts, for example, teaching and learning are seen as involving the direct transmission of knowledge from teacher to student, and questioning is seen as disrespectful.

For those that are high-context communicators, most of the information resides in the physical setting, or is seen as internalized in the person. Consequently, the meanings of communication are mostly implicit, so there is no point in using direct and straightforward messages to disclose the intent of communication. Conversely, low-context communicators require that the contents of the message should be made explicit and information clearly communicated verbally. Depending on the cultural settings of the school, one or other of these approaches will be deemed as more appropriate, and those diverging from the mainstream model of communication will be at risk of marginalization or exclusion.

Additional resources

Resources on Intercultural Communication for Educators/Trainers.

Excercise 1: Exploring Cultral Differences

Excercise 1: Exploring Cultral Differences

Exercise 1: Exploring cultural differences

Watch the following commercials on Youtube.

HSBC Funny Culture ads ( Subway, Bart, Golf ).

HSBC - Italian Flowers (Advert Jury).

HSBC Culture differences Personal space.

believe that italians behave the same as all other europeans.

Please make a list of the points each commercial helps emphasise about cultural misunderstanding.

Thoughts on Intercultural Communication and Teaching

Thoughts on Intercultural Communication and Teaching

In retrospect, interculturalism is not a single aspect of educational provision. It is neither a subject to be given a timetable slot alongside all the others, nor is it appropriate to any one phase of education. Over the last twenty years, intercultural Education and its predecessors (for example, multiculturalism), have been connected to other areas of education policy, such as human rights and gender equality.

What are the challenges? Can an intercultural educational approach negotiate between cultures rather than just point out that there is more than one culture? Is our understanding of intercultural education limited in terms of only referring to nation states or even cities (that is, entities within systems)? Would it be possible to increase awareness of the full range of policies and contexts and of the international environment within which they all exist? Although the nature of intercultural education itself is still controversial, teachers would undoubtedly benefit from reflecting on the complexity of becoming familiar with "a culture".

It is, as mentioned above, not only the immediate context but the wider framework that is too often under-theorized and effectively de-politicized. Take, for example, demographic movement, which covers some of the themes addressed by intercultural education. Demographic movement results from national, and increasingly international, economic, political and cultural forces. From this perspective, achieving a level of adequate intercultural sensitivity requires us to recognize how we can perceive a different set of cultural values and meanings from that of, for example, our students. It also concerns how these worldviews might influence the learning environment.

To explore relationships across cultures within a school, teachers need to increase their understanding of international influences in political debate and educational policy, and of students’ lifeworld's inside and outside the educational institution. In doing so, teacher(s) will strengthen intercultural knowledge and thus promote students’ intercultural experience as well as their own teaching. Teachers’ perceptions are crucial as differences in perceptions of communication, especially with reference to display, discourse and personal disclosure, have a strong influence on classroom activities.

Cultural Diversity

With reference to intercultural communication and teaching in vocational education and training, cultural diversity refers to differences of, for example, language, ethnic backgrounds, or traditions. The understanding of cultural diversity increasingly influences the professional and social life of individuals as well as the internationalization of the labour market. Even though there is not a universally accepted definition of cultural diversity, it is, for example, often associated with age, gender, ethnicity, physical abilities, and sexual orientation of the workforce. With reference to an international understanding of politics, factors such as immigration into Europe and the general process of European integration and mobility have increased both cultural diversity itself, and the discourse around it. Consequently, both educational and labour organizations acknowledge the importance of promoting diversity in education and the workplace.

With reference to linguistic knowledge, students whose primary language at home is different from the national language generally acquire basic knowledge of interpersonal communicational in a short time. Within two to three years, they demonstrate apparent fluency whilst using the national language during social activities in school. In order to address these educational challenges, teachers should be fully aware of the role cultural diversity plays in school. Mastering a mixture of pedagogical and communicative approaches in coordinating class, group that these students may need between five to seven years to achieve the necessary level of cognitive academic language proficiency. and individual activities will promote intercultural sensivity in educational settings.

Additional resources:

Further Reading and References

Further Reading and References

Baker W., Culture and Identity Through English As a Lingua Franca: Rethinking Concepts and Goals in Intercultural Communication, De Gruyter, Boston 2015.

Bennett, J. M., & Bennett, M. J. (2004). An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. Handbook of intercultural training, 147-165.

Chen L. (Ed.), Intercultural communication, De Gruyter Mouton Boston, Massachusetts / Berlin, Germany, 2017

Coulby, D. (2006). Intercultural Education. Theory and practise. Intercultural Education, 17:3, 245-257, DOI: 10.1080/14675980600840274.

Croucher S. M. (Ed.), Global perspectives on intercultural communication, Routledge, New York, London, 2017

Cushner, K., & Mahon, J. (2017). Intercultural Competence in Teacher Education.

de Albuquerque M., Ana M., Jean-Jacques P., Nigel B., Intercultural Studies in Higher Education: Policy and Practice, Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2019.

Faas, D., Hajisoteriou, C., & Angelides, P. (2014). Intercultural education in Europe: Policies, practices and trends. British Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 300–318.

Rings G., Rasinger S., The Cambridge Handbook of Intercultural Communication, Cambridge University Press, 2020

Multicultrual Learning. Resource.

Module 3: Digital Media in Teaching and Learning

Introduction to Digital Media in Teaching and Learning

Introduction to Digital Media in Teaching and Learning

Course Objectives

After having taken the course, the student should be able to:

Cognitive learning objectives (Bloom):

- describe and give examples of a few digital models and be able to apply these to their own teaching

- evaluate whether a particular digital activity in teaching fullfils the criteria for meaningful learning and self-regulation

Affective learning objectives (Krathwool)

- contribute to and create a safe learning environment for vocational students and themselves as VE-teachers

- integrate digital resources in meaningful ways that support the individual, the group and their learning

Psychomotor or kinesthetic objectives (Harrow)

- be able to technically produce an interactive notice board and a blog for pedagogical use

- be able to implement digital theories and models in creating an interactive notice board and a blog

- be able to take into account current and local legislation within copyright and GDPR within all use of technology and media in their own teaching and subject

Introduction

This is a short introductory OPVET video (10:34), where the two teachers in this course: Professor Petri Salo and Researcher and IT-Pedagogue Johanna Björkell introduce themselves and the course.

Learning Processes and Digital Media

The complex and versatile learning processes for achieving competencies and being able to use and develop them within a certain profession (hairdressing, plumbing, accounting, marketing, etc.) take place in at least three complementary learning environments. Learning a profession and achieving competence takes place:

- in traditional face-to-face communication and interaction, and tasks performed in schools and classrooms,

- in relation to guided and facilitated learning processes at workplaces,

- within various forms of mediated teaching and learning on educational platforms or social media.

Digital media/ICT is nowadays available, and presents itself as a flexible opportunity and resource, enhances openness, makes it possible to bridge and blend learning taking place at schools, workplaces and even during leisure time. The range of and the opportunities for using digital media within VET (Vocational Education Training), are numerous. Still, no matter the kind of learning environment, they all consist of four interrelated aspects, to be taken into consideration when planning, conducting and assessing activities aimed at learning. These aspects are:

Physical aspects, firstly buildings, classrooms, furniture and various kinds of educational equipment, and secondly technologies and material, ranging from pencil and paper, to computers, instruments, machines, smartphones, apps and digital learning platforms online.

Psychological aspects, which can be divided into cognitive aspects (teachers and students’ knowledge and skills), and affective aspects, (teachers and students´ ambitions, motivation and emotions)

Social aspects, consisting of relationships, interaction, collaboration between people engaged in the learning environment at hand.

Cultural aspects, principles and practices, modes of actions and routines, of which some are tacit and some explicit.

All learning environments within vocational training are organized in order for the students to reach the competencies formulated as learning outcomes. The process of reaching the learning outcomes include certain components and is organized in a following manner:

Tasks to be performed

Processes to be engaged in

Resources to be made use of

Assessment for establishing if the learnings outcomes have been reached (quantitatively – to which extension? qualitatively – in what manner?) are finally utilized.

Learning Environments

Learning Environments

In the following OPVET video (10:48), you will learn about the house metaphor and how you can use that metaphor to plan, execute and assess your course, as well as add digital aspects in a meaningful way to your teaching (your house). You will also learn how to create well-organized, motivational and meaningful learning environments regardless of if they are online, in real life (IRL) or blended.

Competencies for Digital Learning

Competencies for Digital Learning

In this OPVET video (14:36), you will hear a discussion on what kind of competencies, you as a VET teacher will need to successfully navigate digital media and technology in teaching. This video covers the range of competencies needed as well as the ADDIE-model.

Models for Relating to Digital Media

Models for Relating to Digital Media

Integrating Technology in Education

"Effective integration of technology is achieved when students are able to select technology tools to help them obtain information in a timely manner, analyze and synthesize the information, and present it professionally. The technology should become an integral part of how the classroom functions -- as accessible as all other classroom tools."

National Educational Technology Standards for Students, International Society for Technology in Education

TPACK-model

TPACK stands for Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge and shows what skills you as a teacher need in order to use technology and media in a meaningful way in teaching and learning. The theory has been developed by Mishra and Kohler (2006).

Here is a short introductory video on how the theory works by Common Sense Education (2016).

SAMR-model

SAMR is an abbreviation of Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition and is used in relationship to at what level you are digitalizing, as you can use technology and media at a very low level of digitalization or at a very high level. This model shows you how to move from a lower level to a higher level in your own teaching and use of digital media.The model was popularized by Dr. Ruben Puentedura.

The following video outlining the SAMR-model was created by Common Sense Education (2016).

The Star Model, Meaningful Learning and an Example Course

The star model (Majava, 2005) is a Finnish model to outline how to best structure teaching when considering the many various ways that we, as teachers, provide our students with resources and material, sometimes in the classroom, on the board, on the screen, in an E-mail or on a learning platform such as Moodle, Canvas, Its Learning, Showbie, etc, or on a webpage or in a blog.

The Star Model is one of the models we discuss in the following OPVET video (16:36) along with meaningful learning and an example of a course model.

Self-Regulation and Empowering Students

Self-Regulation and Empowering Students

The following is a discussion with Post-Doc Researcher and PhD Annika Wiklund-Engblom about self-regulation in terms of students' motivation to take a part or all of their studies online, as well as how you as a VET-teacher can motivate and empower your own students.

Tools - an Overview for Educational Purposes

Tools - an Overview for Educational Purposes

There are so many tools out there. Your teaching carreer and experience will only lead you deeper into the vast possibilities. But to counteract overwhelm, let's look at what the basics are. What do you REALLY need to know. And what can you save until later.

Here is our list of 11 basic tools for the VET teacher. But really, for any teacher.

11 tools presentation by Johanna Björkell.

And here is a video where I explain why these 11 tools are worth your time and effort.

Copyright, Creative Commons and GDPR

Copyright, Creative Commons and GDPR

Part 1 of copyright for teachers –Google image search

There is a right and a wrong way, for both teachers and students, to use images from Google image search. In this OPVET video (9:16), you will learn how to do it the right way. Remember to teach your students this as well! This is not common knowledge yet.

Part 2 of copyright for teachers – Creative Commons

In this OPVET video (14:32), our need for various forms of media (images, videos, music, sounds etc) continues in the form of learning how to use the search engine CC Search or Creative Commons Search engine in stead of Google. This makes it safer for you and for the students.

Part 3 of copyright for teachers – resources

This OPVET video (8:50) deals with overall copyright issues for teachers, which is a very complex subject and can vary a lot between the Nordic countries, so make sure that you are up to date with your local legislation on the subject. The video includes some tips on resources available in each country.

GDPR - youth and children online- part 1

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a newly implemented standard on how different actors can and should use data collected. This includes schools and educational providers and is very much something you need to be more knowledgable about. This OPVET video (14:26) is just a short introduction into the subject:

GDPR - youth and children online- part 2

In part two of the OPVET video on GDPR and working with youth online, we look at some general recommendations on how to work with young people regarding various digital media and social media.

All five films are:

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The films were produced by Johanna Björkell, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

Blogs in VET

Blogs in VET

Blogs can be a great tool in education as long as you know a few of the tricks: using a simple tool to do it (Wordpress and Blogger are for advanced bloggers, there are easier tools, we present 1 in depth below), setting up blog buddies or blog groups so you do not have to comment on every single post for every student, fostering for a good climate when students are commenting on each other's posts, and how to integrate the blog into face-to-face teaching.

The following OPVET video (10:50) talks a bit more about the things you may want to know before you start your own blog project as a teacher.

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

Create a Weebly blog part 1

Weebly is a free service online, in which you can (easily) create webpages and blogs and webpages and blogs combined without having to know any coding whatsoever, you only drag and drop the different elements on the page. The service is free (with certain constraints of course) but is very usable in educational contexts, for yourself or your students. Another example is wix.com, but in terms of technical usability and user friendliness weebly.com is better.

The following OPVET film (13:56) shows you how to create your account and set up your blog. This video is well suited to be used with your students as well.

Create a Weebly blog part 2

This OPVET video (14:57), shows you how to work with the actual blog page of your Weebly site.

Create a Weebly blog part 3

In this final part of the series (6:21), we will take a look at an actual example used at Åbo Akademi University and the vocational teacher training program's use of blogs as a pre-service training report tool. This shows you how you, as a teacher, can place many blogs in the same blog.

All of these videos are:

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The films are produced by Johanna Björkell, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

Interactive Noticeboards in VET

Interactive Noticeboards in VET

Create an interactive notice board - Padlet

An interactive notice board is a digital version of the notice board that you have in your school lobby, where notices about job offers, bikes for sale, concerts, school rules and sometimes grades are displayed. The version in your school lobby is restricted to text and images (and non-functional URL-links you have to write in yourself in a web browser or QR-codes that you can scan with your mobile device). The digital version, however, can contain images, text, videos, sound files, links etc, and can be used in a very wide range of pedagogical tasks or presentations.

In the following OPVET video (7:59), we will look at the pedagogical uses of an interactive notice board.

Familiarize yourself with the interactive notice board service Padlet in this OPVET video (13:31).

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is produced by Johanna Björkell, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

Videos (for Digital Storytelling)

Videos (for Digital Storytelling)

We could have tried to make these videos ourselves, but there are better experts out there to show you how. We are not experts on creating videos. Learn how to "YouTube" and ask yourself: "best way to shoot from above with a phone" or whatever it is that you wish to shoot a film of, you'll be surprised at what you might find!

First something on how to tell a digital story by WeVideo.

Here, a quick tutorial on how to make great instructional videos by Pond5.

How to make lesson videos, screen recordings in less than 6 minutes by Andrew Borne.

The process is pretty much the same on any phone but you could do a YouTube search for your specific brand of phone too.

Creating an Online E-Course from Scratch

Creating an Online E-Course from Scratch

The following is a 45 minute lecture in Swedish on how to create effective online courses for e-learning, it contains some of the concepts that we have discussed in the present course.

This part of the course is very much so voluntary, but might contribute with some added value.

This video was created within another project, GEM-brickan, among Swedish-speaking vocational schools in Finland (Axxell, YA!, Prakticum and Optima), was financed by Svenska Kulturfonden and can be shared only here with kind permission by them and the creator Johanna Björkell.

© Svenska kulturfonden, Practicum, Axxell, Optima, YA!, GEM-brickan, Johanna Björkell

The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

Föreläsningen med it-pedagog Johanna Björkell är producerad för projektet GEM-brickan, inom vilket yrkesskolorna Axxell, Optima, Prakticum och YA! samarbetar, och där Svenska Kulturfonden är huvudfinansiär.

Summary and Conclusions

Summary and Conclusions

In this final OPVET video (4:09), Johanna Björkell and Petri Salo summarize the course and the teachings.

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

If you wish, any thoughts and comments you may have on Module 3, you can state in this short survey with only 3 questions.

Congratulations on finishing this course!

Further Reading and References

Further Reading and References

OPVET Course Content

- OPVET Intro

- OPVET Learning Environments

- OPVET Models for Relating to Digital Media

- OPVET Competencies for Digital Learning

- OPVET Blogs in VET

- OPVET Interactive Notice Boards in VET

- OPVET Summary

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

Screencasts

- Create a Weebly blog part 1

- Create a Weebly blog part 2

- Create a Weebly blog part 3

- Create an interactive noticeboard - Padlet

- Part 1 of copyright for teachers – Google image search

- Part 2 of copyright for teachers – Creative commons

- Part 3 of copyright for teachers – resources

- GDPR - youth and children online- part 1

- GDPR - youth and children online- part 2

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is produced by Johanna Björkell, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

Other videos in the material

© 2018 OPVET, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training

The film is created by Johanna Björkell, Åbo Akademi University, Vocational Education Teacher Training and Annika Wiklund-Engblom, Umeå University. The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

Skapa effektiva e-lärandekurser

© 2018 Svenska kulturfonden, Practicum, Axxell, Optima, YA!, GEM-brickan, Johanna Björkell. The film is produced by Magnus Blusi at Edulab, the Academic Library Tritonia

© 2016 Common Sense Education

© 2016 Common Sense Education

Further reading

- https://www.bios-project.eu/site/en/vooc/index.html

- https://www.virtual-college.co.uk/search?q=VOOC

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1073188.pdf

- https://www.educationworld.com/a_issues/chat/chat262.shtml

- https://creativecommons.org/2010/09/09/do-open-educational-resources-increase-efficiency/

- https://search.creativecommons.org/

- https://www.oercommons.org/

- Picture Capture CC and OER: https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Creative_Commons_and_Open_Educational_Resources

- TPACK

- https://ttf.edu.au/what-is-tpack/what-is-tpack.htmlLinks to an external site.

- http://www.rt3nc.org/edtech/the-tpack-model/Links to an external site.

- What is the TPACK Model?

- http://blogs.uta.fi/eoppiminen/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2016/09/Klusterin-webinaari_Kirsi-ja-Sanna_PDF.pdfLinks to an external site.

- https://www.edutopia.org/technology-integration-guide-descriptionLinks to an external site.Good source!

Copyright issues for teachers in

Finland

- https://operight.fi/Links to an external site.

- http://kopiraitti.fi/Links to an external site.

Swe:

- https://operight.fi/svLinks to an external site.

- http://kopiraitti.fi/sv/Links to an external site.

Sweden

- https://digitalalektioner.iis.se/lar-dig-mer-om-upphovsratt

- Grundskola och gymnasiet:

- https://www.prv.se/sv/mer-tjanster/for-grundskola-och-gymnasium/

- http://fomp.se/admin/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Upphovsr%C3%A4tt061.pdf

- Högskola:

- https://pil.gu.se/resurser/upphovsratt

- https://sulf.se/faktabank/upphovsratt-en-oversikt/

- Alis – Administration av Litterära Rättigheter i Sverige - www.alis.org

- Svenska Journalistförbundet – www.sjf.se

- Sveriges läromedelsförfattares förbund - www.slff.se

- Stim – Svenska tonsättares internationella musikbyrå - www.stim.se

- Copyswede – Upphovsrättsorganisation för filmare - www.copyswede.se

- BLF – Bildleverantörernas förening - www.blf.se

- BUS – Bildkonst Upphovsrätt i Sverige - www.bus.se

- SFF – Svenska fotografers förbund - www.sfoto.se

- SDF – Sveriges Distributörer av Institutionell Film – www.skolfilm.com

Norway

- https://www.patentstyret.no/tjenester/opphavsrett/

- https://no.wikibooks.org/wiki/IKT_i_utdanning/Opphavsrett

- https://www.uib.no/diguib/79003/opphavsrett-og-undervisning

- https://creativecommons.no/node/33

Iceland

- https://is.wikibooks.org/wiki/H%C3%B6fundarr%C3%A9ttur_og_Interneti%C3%B0

- https://heimildaskraning.weebly.com/houmlfundareacutettur.html#

Denmark

- https://www.emu.dk/modul/copyright-og-ophavsret

- http://undervislovligt.dk/?lang=da

Högskolor

- https://kub.kb.dk/ophavsret/underviser

- http://library.au.dk/underviser/ophavsret

Assignments

Assignments

Potential assignments to be carried out within the scope this course

Firstly

Describe and reflect analytically on your experience, standpoint and your abilities to use and integrate digital media into teaching and learning. Do this in relation the course objectives available on the course platform. Reflect also on the challenges and possibilities, the use of digital media opens up considering VET teachers ́ role and tasks (see the Introduction video)

Secondly

Describe your understanding of learning environments and reflect on what new possibilities the use of digital media opens up for, when it comes to the basic dimensions of learnings environments (see the Learning environments video). Further, according to your understanding, what are VET-teachers core competencies regarding the use of digital media for enhancing student learning within VET? (see the Competencies for Digital Learning video).

Thirdly

Within the section Models for Relating to Digital Media, a range of models for relating and using digital media is presented. Which of these models do you prefer and why? In what manner could you use them for planning and conducting your courses and your teaching?

Fourthly

Watch and make notes of all the videos in the section Copyright, Creative Commons and GDPR. Thereafter sum up the main aspects and criteria on copyright and GDPR in a presentation (Power Point, Prezi, YouTube video) to be presented to either VET –teacher students or VET- teachers.

Fifthly

The material on the platform includes orientational videos and hand-on instructions for the use of either blogs or interactive notice boards (Padlet) within VET-teaching. When thinking of your subject and your teaching experience, which of the two tools would you prefer and why? Reflect on both your choice and your reasoning for it, in relation to the videos. Further, after watching the hands-on instructions on your choice tool, plan, reflect and give examples of specific cases of teaching (themes, procedures, lectures) in which you could use the tool you have chosen.

Sixthly

You ought to either (a) reflect critically on the material available on the platform for this module and the assignments above, or (b) search and present material (videos or reports) with complementary perspectives, models or tools.

Seventhly

A criticism of the ADDIE-model presented in the first part of the module is that it is too linear (models cannot usually accurately portray the complex reality we live in, they provide, as Vygotskij said, only hooks to hang up our understanding on) and that a more organic model could be the KEMP-model. Research this model online (make sure you have reliable sources). Present what it means.Research this model online (make sure you have reliable sources). Contrast the KEMP-model with the ADDIE-model. What is each model's negative and positive aspects? Which one do you prefer to hang up your thoughts and understanding on? Both? Motivate your answer.

You can document your standpoints, choices and reflections in (a) in a traditional written essay, (b) with a ScreenCastomatic presentation or (c) video(s) in which you answer and reflect on the questions formulated above.