Publications - CERG

Research results from CERG

Read the results from our publications.

Studies published in 2023

- Does resting heart rate affect the risk of atrial fibrillation?

- The Fitness Calculator reveals risk of aortic valve surgery

- Do genetics contribute to the health benefits in physically active?

- What do our fitness genes say about disease risk?

- Exercised blood stimulates to brain cell formation in rats with Alzheimers disease

- Patients with heart failure are able to attend digital exercise sessions

- Endurance athletes live longer

- Micro-RNA 133b is linked to more vulnerable coronary plaques

- Could subfractions of lipoproteins reveal future heart attacks?

- What does lipids in blood tell us about the lipid content of coronary plaques?

- Measuring fitness can give more precise cardiac diagnostics

- Exercise did not improve blood vessel function in heart failure

- More research needed to establish fitness genes and their impact on health

- The older you are, the faster your fitness declines

- Moderate exercise may be better for older adults' brain health

Studies published in 2022

- 4x4 interval training reduced atherosclerosis in heart patients

- 4x4 interval training improves health in common liver disease

- Improved fitness and activity levels following obesity rehabilitation

- Low stroke risk among veteran endurance athletes

- 100 PAI links to lower risk of a heart attack

- Interval training changes gene expression in the heart of smoke-exposed mice

- Identified a gene that affects both fitness and body weight

- Interval training in heart failure led to muscular changes that can improve fitness

- One in four covid-19 patients still have reduced physical capacity after one year

- Does etiology influence exercise response in heart failure?

- Coud Calanus oil supplementation increase physical fitness?

- PAI could be a great tool against dementia

- Does change in fitness affect medication for mental health issues in the elderly?

- How does exercise intensity affect signal conduction in the brain of the elderly?

- Interval training for heart failure patients improves the function of HDL particles

- Does kidney function influence exercise response in heart failure?

- Does hard exercise temporarily impair heart function more in persons with diabetes?

- Does interval training reduce vulnerable plaques in coronary arteries?

- New fitness genes found in record-breaking analysis

- High fitness can protect the elderly from structural brain impairments

- The higher cardiorespiratory fitness, the lower is the risk of heart surgery

- Micro-RNA and plaque burden change in interaction after exercise

- Impaired heart function is more common following severe covid-19 disease

- Low fitness is linked to adverse lipid profile

- Organized exercise dit not reduce progressive of white spots in older adults' brains

- Can blood plasma from fit donors help us treat Alzheimers disease?

Studies published in 2021

- Can gene therapy counteract muscle-wasting in the elderly?

- Can exercice reduce the risk of mild cognitive impairments among older adults?

- PAI is a useful activity standard for the whole world

- Does increasing fitness improve cognitive abilities in older adults?

- Does interval training lower cardiovascular risk more in older adults?

- Older men improved HDL cholesterol with interval training

- Blood test can reveal exercise response in heart failure

- What are the main reasons for impaired fitness after covid-19?

- Can exercise attenuate loss of brain volume in older adults?

- Walk test provides useful information on fitness after stroke

- Does hard exercise increase atrial fibrillation risk via effects on the immune system?

- How does high-intensity training impact walking and balance following stroke?

- Could carbohydrates make you run faster and longer?

- Does lung function impact cardiorespiratory fitness in COPD?

- Can your genes predict how you will respond to endurance training?

- Increased muscle-degrading activity in heart failure

- Has uncovered important mechanism for exercise response

- Could you exercise hard following pulmonary embolism?

- 70-year-olds with good fitness have higher blood volume

- Moderate exercise might benefit stiff, failing hearts the most

- Is high-intensity training harmful to failing hearts?

- Can 100 PAI prevent excessive weight gain?

- How does cardiorespiratory fitness impact life expectancy in people with arthritis?

- How should patients with diastolic heart failure exercise?

- Do women with heart disease benefit as much as men from high-intensity interval training?

Studies published in 2020

- Lives several years longer when PAI score is kept above 100

- Faster age-related decline in fitness among people with rheumatoid arthritis

- Does exercise make older adults live longer?

- Fitness declines less with age in active persons

- Interval training strengthens several functions in failing hearts

- Who are most physically active: Norwegian or Brazilian older adults?

- Knowledge from exercise can lead to new heart drugs

- Also Americans live longer with 100 PAI

- Could 4x4 interval training after a heart attack improve cardiac filling?

- Is exercise good medicine for cancer patients?

- Does lung function affect fitness in heart patients?

- What do we know about high-intensity interval training and youths?

- What do we know about high-intensity interval training and brain health?

- Exercise could reduce coronary artery plaques following stent implantation

- Is 4x4-minute interval training beneficial after a stroke?

- Persons with atrial fibrillation benefit from exercise and high fitness

- New fitness genes link to cardiovascular health

- Fitness predicts atrial size

- New Fitness Calculator for rheumatoid arthritis

Studies published in 2019

- What is the average fitness level of healthy men and women?

- How much does maximum stroke volume decrease with age?

- Lower exercise response in older and severely ill patients with heart failure

- Low fitness is an independent risk factor for dementia and death from dementia

- Change in high-energy phosphates is not suited to evaluate exercise effects in heart failure

- Miniscule molecules in blood could reveal heart attack risk

- Reduced risk of atrial fibrillation with high fitness

- Is weight gain harmful for the physically active?

- Reduced fitness in rheumatoid arthritis

- Does high fitness prevent myocardial infarction in both men and women?

- Is exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis normally dangerous?

- Regular runners have optimal lower body mitochondrial function

- Links poor fitness to increased inflammation

- High-intensity training restores myocardial mitochondrial function in diabetic mice

- Higher fitness linked to higher brain volume

- Exercise affects skeletal muscle metabolism in rats with heart failure

- Could exercise help oss develop new drugs against heart failure?

- How could exercise prevent and treat Alzheimer's disease?

- 100 PAI seems to secure high age-specific fitness

- Poor fitness predicts early death in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Could skiers double pole to better fitness?

- What kind of exercise is most likely to increase fitness?

- Lung function could affect the physical capacity in healthy persons

- How can high fitness protect against metabolic diseases?

- Could a litte exercise improve skeletal muscle metabolism?

- Also healthy people avoid heart attacks by staying fit

- Is the maximum heart rate higher with lower fitness?

- Motivational interviewing helps stroke patients maintain physical activity

- 4x4 intervals improve fitness and body composition in psoriasis arthritis

- Increased risk of dementia in physically inactive persons with high psychological distress

- Lived longer after increasing the PAI score

- What kind of exercise does older adults prefer?

- Can exercise restore normal muscle function in heart failure?

- Also heart patients with 100 PAI live longer

- Should individuals with atrial fibrillation exercise?

- Which older adults are more likely to drop out of an exercise program?

- Does weather influence physical activity in the elderly?

- Can physical activity prevent atrial fibrillation?

- Can exercise prevent newborns' cardiac dysfunction following obese pregnancies?

- Exercise is linked to less dementia-related death

- How to exercise with peripheral artery disease

- The fit and happy live longer

- Heart patients live longer if they stay physically active over time

- Heart failure: Higher increase in oxygen uptake following high intensity interval training

- Effective high intensity interval training in obese children

- Rats escaped atrial fibrillation following high intensity interval training

- Should heart patients exercise the day before surgery?

- Obese children strengthen week hearts by exercising

- Why do failing hearts struggle during strenous acitivty?

The lower the resting heart rate one is genetically predisposed to have, the higher is the risk of getting atrial fibrillation. Low genetic resting heart rate is inherited randomly and thus not influenced by lifestyle and environmental factors that can change the resting heart rate. Thus, we can say with considerable certainty that it is a low resting heart rate in itself that increases the risk of future atrial fibrillation.

Previous studies have confirmed 46 genetic variants that are linked to a low resting heart rate, and these were the starting point for our analyses. In the study, we have examined genes and other health data in almost 70,000 women and men who participated in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study between 1995 and 2008. We have also carried out the same investigations with data from the UK Biobank, where over 430,000 Britons contributed between 2006 and 2010.

By 2016, around 7,000 people from Trondheim had been confirmed to have atrial fibrillation, while more than 20,000 Britons had atrial fibrillation by 2021. Those who were genetically predisposed to the lowest resting heart rate had the highest risk. For each beat higher resting heart rate, the risk decreased by 4–5%. Very few people were genetically predisposed to a higher resting heart rate than 90, so we cannot say whether the risk of atrial fibrillation continues to decrease even with resting pulse values above 90.

Although a high resting heart rate in itself seems to protect against atrial fibrillation, it is not those with the highest resting heart rate in the population who have the lowest risk of getting atrial fibrillation. Both resting heart rate and risk of atrial fibrillation are affected by how we live, for example via blood pressure, BMI, smoking habits and level of physical activity. If one studies the link between resting heart rate and atrial fibrillation without taking these factors into account, it is those who have a resting heart rate between 60 and 80 - measured while sitting during the day - who have the lowest probability of getting atrial fibrillation.

The better the estimated cardiorespiratory fitness, the lower the risk of having to undergo aortic valve surgery. Aortic valve surgery is carried out in severe aortic stenosis, where the aortic valve is calcified and narrow and needs to be replaced. The study also shows that those who have undergone aortic valve replacement live longer if they have high fitness to begin with.

The study includes 57,214 men and women who participated in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study in the mid-1990s (HUNT2) and/or in 2006–2008 (HUNT3). By 2018, 102 went through aortic valve surgery, and 35 of these died by April 2020.

We used the Fitness Calculator to estimate the fitness level of the participants. For every increase of 1 MET the risk of surgery was 15% lower. The 20% who had the highest estimated fitness for their age had more than halved the risk, compared to the 20% with the lowest fitness. The risk of early death after aortic valve surgery was 37% lower per 1 MET increase in estimated fitness level.

Genes that increase the likelihood to be physically active are also linked to a healthier health profile. Specifically, we found that the risks of stroke, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are lower the better activity genes you have. In addition, we linked better activity genes to healthier waist circumference, BMI and HDL cholesterol. Among other things, the analyzes were adjusted for self-reported level of physical activity among the study participants. Thus, the results may indicate that some of the health benefits in physically active people are genetic - and not caused by the physical activity itself. Nevertheless, the effect sizes were low for all the associations, and it is uncertain if the findings have any clinical significance. Further, we found no correlation between having good activity genes and directly measured cardiorespiratory fitness levels.

The study, which has been carried out in collaboration with Finnish researchers, uses data on genes, physical activity and risk factors from nearly 50,000 people who participated in the Nord-Trøndelag Helath Study (HUNT) between 2006 and 2008. All participants were given an overall score based on a number of gene variants that have previously been shown to be important for physical activity levels. We then investigated how this score relates to a number of health variables today and the risk of developing disease up to ten years in the future. There is some uncertainty linked to the findings, partly because the genetic activity score did not explain particularly much of the actual physical activity level of the participants in HUNT.

Genes that are linked to high fitness can also be linked to other things that affect our health. For example, our findings suggest that fitness genes also have an effect on the levels of creatinine in the blood and the risk of developing type 1 diabetes. We also found less certain signs that good fitness genes can lead to lower BMI, healthier levels of HDL cholesterol and lower resting heart rate.

We previously published the world's largest analysis of gene variants associated with directly measured fitness. In the new study, we investigated whether the 22 gene variants that were most closely linked to maximum oxygen uptake in that study are also linked to other measures of health. 65,000 participants from the second and third round of the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study have contributed data to the analyses. In addition to data from the health survey itself, we have also obtained information about hospital-registered diagnoses for the same people between 1999 and 2017.

Three of the gene variants that are linked to good fitness could also be linked to increased levels of creatinine in the blood. Increased levels of creatinine are associated with increased muscle mass. We can speculate that these three gene variants have an effect on muscle mass and in that way both give increased levels of creatinine and higher VO2 max. We checked the findings by doing the same analyses in a large British database, and found that two of the same gene variants were linked to increased creatinine levels. The analyzes from HUNT further indicate that a gene variant that increases fitness can significantly increase the risk of type 1 diabetes with neurological manifestations.

When we examined 33 gene variants that are only associated with fitness in men, we found that four of them are also linked to a significantly increased risk of endocarditis, an inflammatory disease of the inside of the heart. It is not unusual for genes linked to good health in one area to be bad for health in one or more other areas. For women, we found no reliable relationships between 44 gene variants and other health variables.

Although we did not find many reliable connections, we did make several interesting findings that have lower statistical power. Among other things, we saw signs that some of the genes that can give high fitness can also give a lower BMI for both sexes and healthier levels of HDL cholesterol and a lower resting heart rate for women.

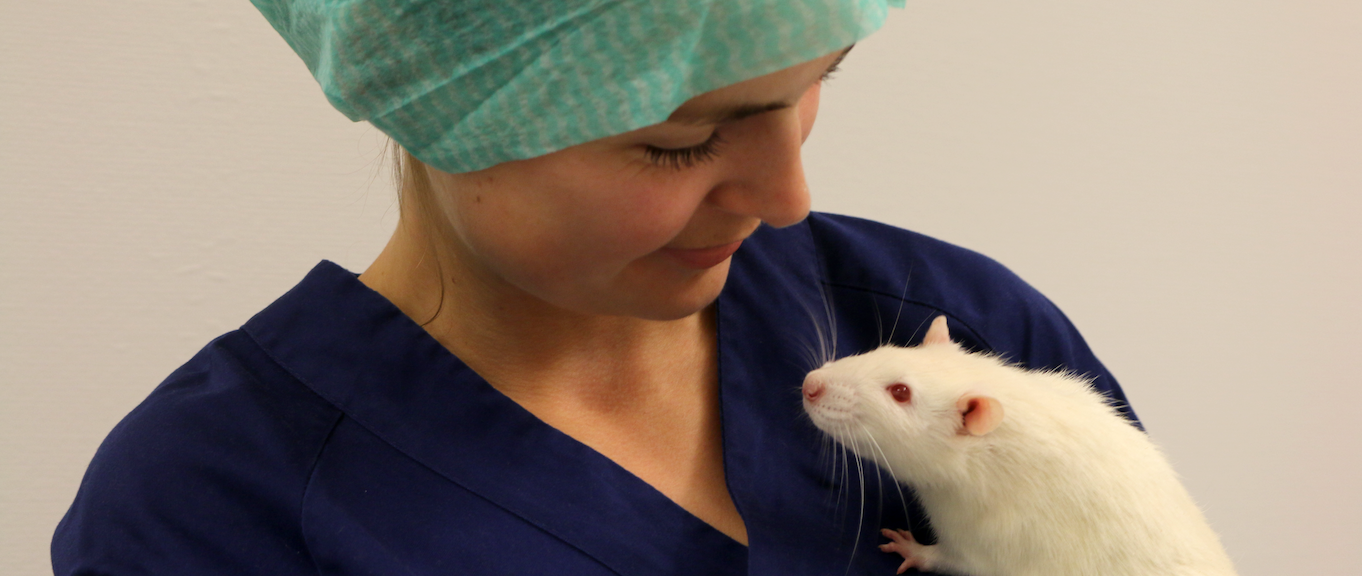

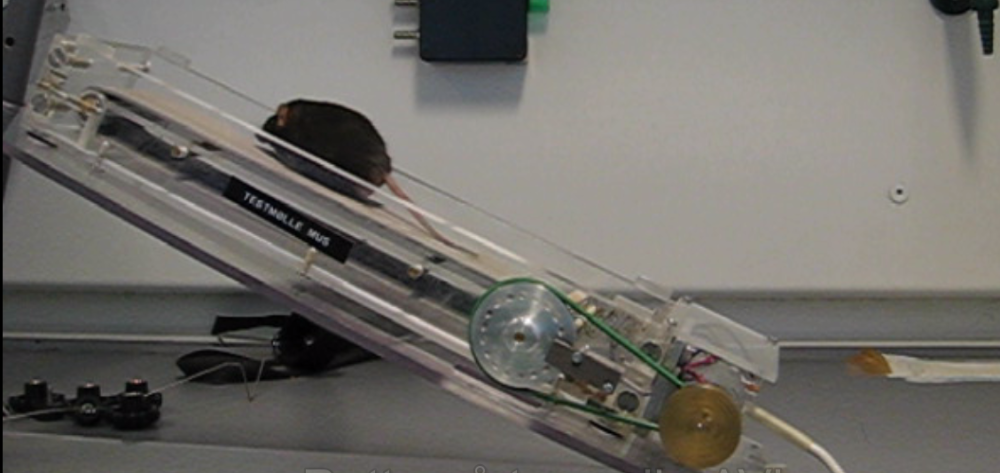

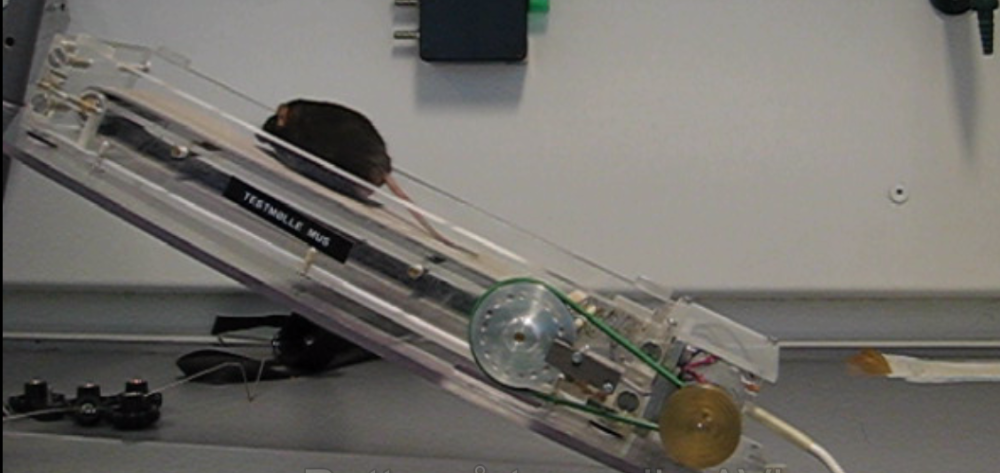

Blood plasma from men who have recently exercised counteracts impairments in Alzheimer's-like brain cells of mice. The brain cells from the mice were exposed to amyloid-β to simulate the damaged caused by Alzheimer's disease. Subsequently, the cell cultures were treated with plasma from endurance-trained men who had provided blood samples both before, immediately after, and up to one day after an intense workout. It turned out that the exercised blood prevented the mouse brain cells from shrinking in size and led to a higher proportion of healthy brain cells. This effect was most pronounced in the blood collected three hours after the exercise session.

We also transferred blood from rats that had performed six weeks of high-intensity interval training to rats genetically modified to develop symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. The rats received a total of 14 injections of exercised blood over six weeks. The rats that received the exercised plasma showed over a threefold increase in the formation of new brain cells in the hippocampus, compared to rats injected with saline solution. The hippocampus is a part of the brain important for short-term memory and learning, among other functions. This effect applied to rats that had not yet developed symptoms of Alzheimer's disease, as well as rats in a later stage of the disease.

Reduced inflammation could possibly be part of the explanation why exercised blood contributes to better brain health. The interval training led to lower levels of seven inflammation-inducing cytokines in the blood. Despite the increased formation of brain cells in the hippocampus, the injections with exercised plasma did not improve the rats' cognitive abilities. Trained plasma also did not reduce Alzheimer's-related plaques in the brain.

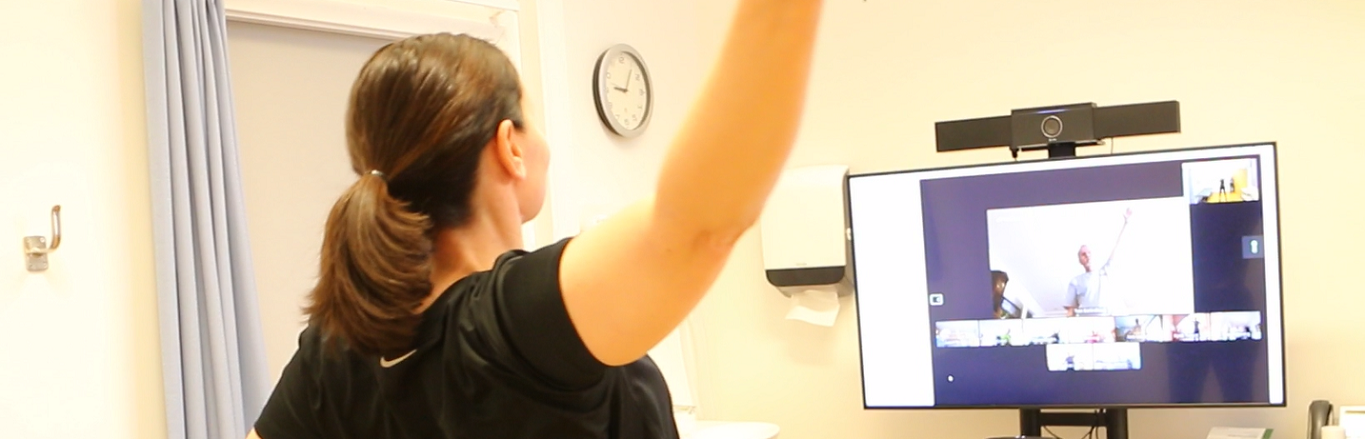

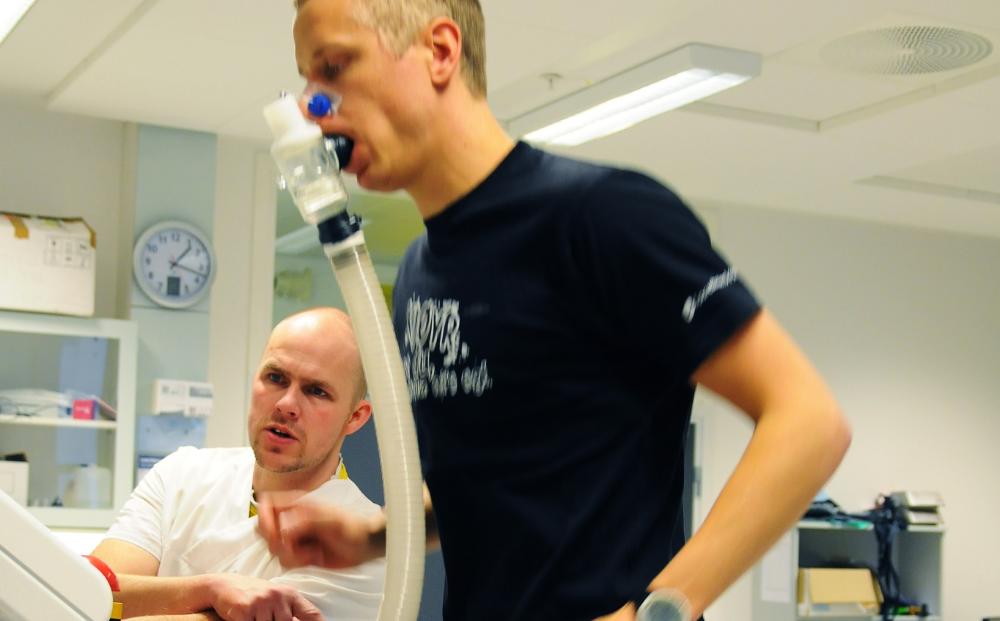

80% of heart failure patients who were offered home-based telerehabilitation participated in most of the exercise sessions. No one got sick or injured during the sessions, and almost all reported that they felt safe and wanted to continue exercising after the period of digital exercise follow-up ended. The results show that it is entirely possible for elderly patients with heart failure to take part in live exercise sessions with a physiotherapist via video link.

61 patients with heart failure participated in the study. The participants did not have the opportunity or desire to participate in the exercise groups at the hospital, but wanted to try home-based exercise. All attended a two-day course on how to live as well as possible with heart failure, but only half were given a tablet and offered to join digital exercise sessions directly from their own living room. Two days each week they could do intensive interval training via video transmission together with a physiotherapist, and the goal for everyone was to achieve 24 sessions.

The training was performed according to the 4x4 principle, with a focus on exercises for large muscle groups – for example, deep squats and fast walking or running on the spot.

Around 40% of the participants reached 24 sessions within four months, while another 40% took a slightly longer period to reach their goal. We also encouraged the participants to be active outside of the live exercise sessions. Among other things, they had access to pre-recorded exercise sessions on their tablet. They were asked to use these resources even after the period of supervised video exercise was over.

After the training period, the participants in the exercise group had improved by an average of 19 meters on a six minute walk test, but the control group improved by about the same amount. After another three months, we measured their maximum oxygen uptake. The participants in the training group had the same level of fitness as when the study started, while the control group had a significantly worse level of fitness. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant.

Thus, we can state that home-based telerehabilitation is feasible for patients with chronic heart failure. Our study also gives no indication that such training is not safe. However, the results cannot yet confirm that it is also more effective in improving physical fitness, compared to regular follow-up.

Veteran cross-country skiers live longer than other physically active men

Veteran cross-country skiers live longer than other physically active men

Older men who engage in endurance sports competitions have a significantly increased chance of surviving the next ten years - even when compared to physically active men who do not participate in sports competitions. The findings may indicate that many years of active exercise and competition provide additional health benefits compared to training in line with the authorities' minimum recommendations.

In total, the study includes data from 2,370 men older than 65 years. 503 of them took part in the Birkebeiner cross-country ski race in 2009 and 2010 and were defined as athletes, while the other 2,757 took part in the Tromsø 6 survey between 2007 and 2008. After ten years of follow-up, 7% of the athletes had died, compared to 32% of the men from Tromsø. After taking into account that the athletes on average both had a higher education, smoked less and drank less alcohol, the risk of early death was still 66% lower than for the Tromsø men. Even lower BMI, medication use or the occurrence of diabetes and heart attacks could not explain the reduced mortality among the athletes.

In further analyses, we saw that the risk of early death was highest among the Tromsø men who reported being physically inactive. But we also saw that the men from the Birkebeiner race had roughly halved the risk compared to participants from Tromsø who reported a similar level of physical activity. The Tromsø participants who reported the highest level of physical activity had 57% lower risk of early death compared to those who were inactive, whereas the risk reduction among the the cross-country skiers who exercised the most was 79% .

The study is part of the NEXAF initiative, where our researchers collaborate with researchers from Bærum Hospital and the University of Tromsø.

Micro-RNA in the blood can reveal dangerous plaque in heart patients

The more fatty plaques the heart patients had in their coronary arteries, the higher were the levels of micro-RNA 133b in their blood. Thus, a blood test that analyzes this micromolecule can possibly help us to identify which patients are at high risk of having plaques that are likely to rupture and cause a heart attack.

Micro-RNAs are tiny molecules that regulate the activity of our genes. There are several thousand such micromolecules, and in our study we measured the levels of 160 different micro-RNAs in 47 patients with stable coronary artery disease. We also took ultrasound images of the inside of the patients' coronary arteries, and with the method of near-infrared spectroscopy we found the most fatty plaques.

Of all the microRNAs we examined, it was microRNA 133b that was most closely linked to plaque lipid content. The correlation was not weakened when we adjusted for traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. This suggests that micro-RNA 133b itself can reveal fatty plaques, but the strength of the association was moderate, and larger studies are needed to provide firm conclusions.

Among middle-aged and elderly people with a low risk of heart attack, we found no definite relationship between the levels of 112 different lipoprotein particles and future heart attack. In addition to looking at the total levels of, for example, LDL and HDL cholesterol in the blood, we divided these classic lipoproteins into groups based on size, density and concentration of lipids in the lipoprotein particles. Thus, we had the opportunity to look at whether, for example, small and dense HDL and LDL particles with a high concentration of cholesterol and other fatty substances were differently associated with heart attack risk than larger and less dense particles with a low fat content.

The study includes 50 people who had a heart attack within five years despite being healthy and having few or none of the classic risk factors when they participated in the third health survey in Nord-Trøndelag between 2006 and 2008. We compared them with 100 participants who did not have a heart attack within ten years but otherwise were similar to the participants who had a heart attack.

The main analyzes showed no clear connection between any of the 112 subfractions of lipoproteins and the risk of having a heart attack. In less rigid analyses, we found a connection between a high concentration of apolipoprotein A1 in the smallest HDL particles and an increased risk of future heart attack. For men, a low concentration of several lipids in large HDL particles was also linked to an increased heart attack risk. So, although we did not make any definite findings, the results provide a basis for looking more closely at whether subfractions of HDL particles can give us useful information about who is at increased risk of suffering a heart attack.

Lipid levels provide limited information on plaque content in heart patients

Using advanced analyses, we found two types of lipid particles that can potentially tell us something about the lipid content of plaque in patients with stable coronary artery disease. The patients with increased levels of lipoprotein(a) in the blood had, on average, slightly more fatty plaques in the heart's coronary arteries than patients with normal lipoprotein(a) levels. In addition, higher levels of free cholesterol in the smallest HDL particles were also associated to some extent with increased plaque lipid content. The two fatty substances did not, however, give us additional information about the plaque content beyond what we got by measuring traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Fatty plaques are more unstable than plaques with less fat, and thus increases the risk of a heart attack. However, it is difficult to measure the plaque content in the coronary arteries accurately, and it would be very useful to find biomarkers in the blood that can tell whether the calcifications contain much or little fat.

In the study, we examined the levels of 114 different lipoprotein groups in 56 patients with stable coronary artery disease. The analyzes does not only look at the levels of, for example, plain LDL and HDL cholesterol, but also the size, density and fat content of the various lipoprotein particles. The patients in the study underwent an advanced, invasive examination of the heart's coronary arteries, so that we could study the associations between the various fatty substances in the blood and the content of the most fatty plaques in the blood vessels of each patient.

With the traditional method for assessing heart size, nearly all elite athletes met the criteria for pathological left ventricular enlargement, while only 40% of heart failure patients did the same. However, when we took into account the maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) of the participants, the results were completely flipped: None of the elite athletes, but almost all of the patients, had enlarged hearts.

Exercise causes the heart chambers to grow in a healthy and balanced way, unlike pathological enlargement that occurs as a compensatory mechanism in weak hearts. At the same time, we know that larger individuals naturally have larger hearts. The usual method of assessing whether a person has normal heart size is to adjust ultrasound results based on the body surface area of the person. In other words, it takes into account that body size affects the structure of the heart, but not that exercise status also does. In our study, we compared this method to a method where, instead of indexing for body surface area, we indexed for the absolute VO2 max of the participants.

We used ultrasound and fitness measurements from 13 elite athletes and 58 endurance athletes, 1190 healthy men and women, and 61 patients with heart failure. The results from the healthy non-athlete participants were used as reference material for normal and enlarged left ventricular volume, and athletes and heart failure patients were classified based on these reference values.

Among the healthy participants, we found a significantly stronger correlation between VO2 max and left ventricular size than between body surface area and left ventricular size. Using the traditional method, only 24 heart failure patients were defined as having an enlarged left ventricle, while the number increased to 58 (95%) when we used the VO2 max method. For elite athletes, the number of individuals with an enlarged left ventricle dropped from 12 to 0 when we switched measurement methods. The diagnosis was also more accurate for the non-elite endurance athletes, with only one of the 58 having an enlarged left ventricular based on our new measurement criteria, compared to six out of 58 with the traditional method.

Fitness measured as absolute maximum oxygen uptake shows how many liters of oxygen a person can use for energy production each minute. Therefore, this measure takes into account both exercise status and body size. It is not surprising, then, that indexing for VO2 max provides a more precise indication of whether left ventricular size is normal. This new method may prevent the misclassification of healthy hearts as diseased, reducing the need for costly and unnecessary further investigation. There is also potential to use this method in the assessment and diagnosis of heart failure and other heart diseases.

The exercise in our large OptimEx study did not lead to better blood vessel function for the patients. Some patients with heart failure have damaged and dysfunctional blood vessels, and among 159 participants in OptimEx, we measured both the stiffness of large blood vessels, the ability of smaller vessels to dilate, and the function of endothelial cells that line the inside of the vessel wall, in the smallest blood vessels. 70% had impairments in one or more of these measurements, and about half also had reduced levels of cells that repair damaged blood vessel walls.

Neither the group that was assigned to perform 4x4-minute interval training, nor those who exercised with moderate intensity, achieved better blood vessel function during the exercise period. There were no improvements neither after three months of supervised exercise nor after an additional nine months of exercising at home. Furthermore, the levels of markers for repair of endothelial cells did not increase.

The participants in OptimEx have heart failure even though the pumping function of the heart is intact. The main article from the study showed that the exercise resulted in improved endurance capacity (maximum oxygen uptake), despite the fact that the heart did not become better at pumping blood. Since the exercise also did not improve oxygen delivery to the muscles through better blood vessel function, it appears that improved maximum oxygen uptake in this patient group is primarily due to the fact that exercise can improve the muscles' ability to take up oxygen from the blood and use this oxygen for energy production.

Our genes likely determine about half of our maximum oxygen uptake. Our genes also play a significant role in how physically active we are and how our bodies respond to exercise. However, even though we know that genetics are important, we still lack knowledge about which genes affect fitness, activity levels, and training response.

Our researchers have now summarized knowledge from the best and latest studies on genes related to maximum oxygen uptake, physical activity level, and exercise response. CERG have conducted the largest study to date looking for genetic variants associated with directly measured maximum oxygen uptake. We found several individual genes related to fitness, especially in women. Some larger studies have also identified genetic variants that appear to be related to physical activity level measured by activity monitors. However, research has not yet been able to uncover a single gene that can be confidently linked to training response.

The main challenge with these types of studies is that a large number of participants are needed to establish reliable relationships. Since so few fitness and activity genes have been identified so far, we currently know very little about the potential biological mechanisms that could explain why these genes have an impact. This is something our group wants to investigate further in upcoming studies.

We also want to know more about whether fitness and activity genes are also related to other risk factors for heart disease. There are studies suggesting that good fitness may be particularly important for people who have a high genetic risk of developing heart disease. We also assume that exercise and fitness affect the risk of lifestyle diseases by changing the behavior of our genes, known as epigenetics. However, more research is needed before we can provide reliable answers.

Maximum oxygen uptake drops faster as you get older. Based on studies that only measure fitness at one point in time, it has generally been calculated that the fitness number falls by 10% per decade, or by between 0.3 and 0.5 ml/kg/min per year. However, in the few large studies that have measured the fitness levels of the same people twice with several years in between, fitness numbers decline by up to 20% per decade for women and 25% for men aged over 70, while it declines by less than 10% per decade among young adults.

The results are described in a new review article in which our researchers considered all major population studies that have measured oxygen uptake at one or two points in time. The reason why we should rely more on data from studies with multiple measurements is that, to a greater extent, only the healthiest elderly, who are in good shape for their age, will take part in studies with single measurements. Thus, the average maximum oxygen uptake that is measured in the oldest age groups will probably be higher than the real average for the entire population.

Aging in itself, but also the fact that the level of physical activity tends to decrease as one gets older, are likely reasons why the fitness number drops faster with each decade as we get older.

Avoiding very high-intensity exercise and following the health authorities' physical activity recommendations may be the most beneficial for the elderly in terms of keeping healthy brain cells in the hippocampus. After three years of exercise, it was the control group of the Generation 100 study that had the highest N-acetylaspartate:creatine ratio in the hippocampal body, whereas the choline:creatine ratio was lowest in the participants who reported to exercise most intensively.

The neurochemical N-acetylaspartate signals healthy neurons, while choline is important for the cell membranes of the nerve cells. The hippocampus is a part of the brain that, among other things, is important for our memory. However, the differences we found does not seem to have affected the cognitive function of the participants. On the contrary, it was actually the participants with the lowest choline:creatine levels in the hippocampal body who scored highest on the cognitive test.

In the anterior part of the hippocampus, we found no difference in the levels of neurochemicals, neither between the groups nor based on reported exercise intensity. We also investigated whether maximum oxygen uptake had an effect on the metabolites, but neither fitness level at the same time nor changes in fitness over time played any role.

In the Generation 100 study, men and women aged 70 to 77 were randomly allocated to organized exercise follow-up for five years, or to participate in the control group which were told to follow the authorities' recommendations for physical activity. This substudy includes analyzes from 63 of the participants, and we measured the levels of N-acetylaspartate, choline and creatine by performing MR spectroscopy after three years. Most of the participants exercised well throughout the period, and the participants in the control group to a high degree followed the recommendations to exercise with moderate intensity 30 minutes most days of the week.

Interval training can reduce atherosclerosis in heart patients

Regular high-intensity 4x4-minute interval training for six months reduced the amount of plaque in the coronary arteries of patients recently treated for stable angina. This is the first study that has been able to demonstrate that exercise can reduce residual atherosclerosis in patients following treatment for narrow coronary vessels.

The study includes 60 patients. They were randomly assigned to two groups. One half attended guided 4x4 interval training two days a week for six months. The other half received regular exercise advice without any offer of direct follow-up. Both before starting and after six months, we examined the atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries with ultrasound images taken from inside the coronary arteries.

After six months, the interval training had reduced the amount of plaque compared to the control group, where the amount of plaque was unchanged. The training also led to the participants increasing their maximum oxygen uptake by 10%, while reducing their waist measurement by five centimeters on average.

Both the amount of plaque in the heart's coronary arteries and the plaque composition play roles in the risk of having a heart attack. In a previous article, we have shown that the interval training apparently did not stabilize the plaques more than usual treatment, but that the participants who increased their fitness had more stable plaques.

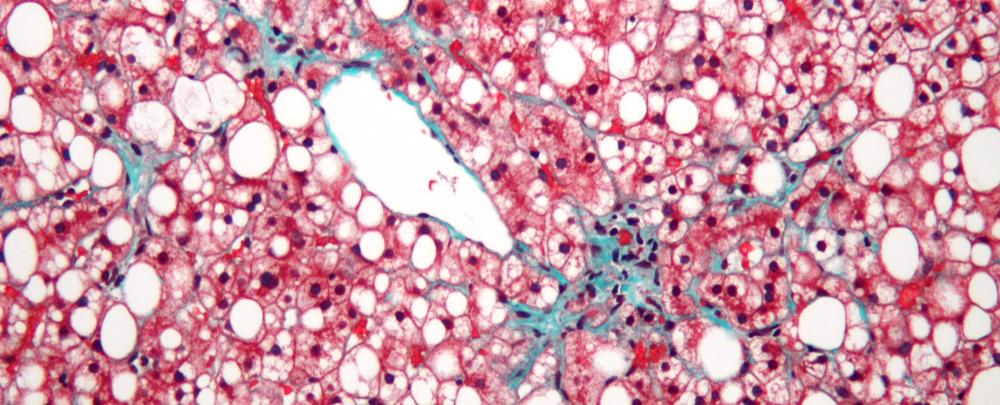

4x4 interval training improves physical capacity and insulin sensitivity in people with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. This is a condition that is common among people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and which involves signs of cell death, inflammation or an increased amount of connective tissue in the liver. In addition, most people with steatohepatitis are insulin resistant and obese.

The pilot study, which was conducted by Australian researchers – including our postdoctoral researcher Ilaria Croci – included 14 participants with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Eight were drawn to complete 4x4 intervals three days each week for 12 weeks. The last six instead met to carry out stretching exercises.

Surprisingly, those who did 4x4 intervals did not increase their maximal oxygen uptake. But on a cycling or walking/running test to exhaustion, they lasted on average two minutes longer than those who had only stretched. The training effect on insulin sensitivity and cholesterol levels was also large, and several areas within health-related quality of life improved.

The study also showed that 4x4 interval training is safe and feasible for this patient group. Furthermore, the interval training led to better liver fat values, lower BMI and reduced waist circumference, although these results were not statistically significant due to the small number of participants.

Both heart function, physical activity level, BMI and maximum oxygen uptake improved for people with severe obesity who participated in a multidisciplinary obesity rehabilitation program. 56 men and women with a high BMI joined the study, and within a year 38 of them completed three three-week stays at the Norwegian Heart and Lung Association rehabilitation clinic at Røros. After both six months and one year, they had lost close to 6 kg on average and also achieved several other health effects.

During their stay at Røros, the participants were followed up by a doctor, nutritionist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and a nurse with expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy. They carried out a number of health talks and received, among other things, theoretical and practical introductions to physical activity.

Many people with severe obesity have hearts that relax poorly between each beat, which can eventually develop into heart failure. However, in this study, where the average age of the participants was as low as 44 years, only six of the participants had impairments so great that they were diagnosed with diastolic dysfunction. Still, after six months, several measures of heart function had improved in the group as a whole, both when it came to the heart's pumping power and ability to relax.

In addition, the average BMI was reduced from approximately 40.5 to 39 kg/m2, while the maximum oxygen uptake increased from 25 to 27 ml/kg/min. The participants had also become more physically active than they were at the start. Importantly, all the changes persisted at one year's follow-up.

Low risk of stroke among veteran cross-country skiers

Although the risk of atrial fibrillation is higher for long-term endurance athletes than for the general population, the risk of stroke is lower. Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke, but the first results from the nationwide NEXAF project now show that older men who have taken part in the Birkebeiner ski race have about 40% lower risk of stroke than men from the general population.

However, the results also show that athletes with atrial fibrillation are more than twice as susceptible to stroke as athletes without atrial fibrillation. This increase in risk is still low compared to most men, where atrial fibrillation is linked to a fourfold risk of stroke.

The findings are based on data from more than 500 athletes from all over the country and close to 2,000 men of the same age from Tromsø. All the athletes were over 65 years old when they took part in Birkebeinerrennet in 2009–2010. On average, they had participated in 14 editions of the ski race. All answered a questionnaire about exercise, other lifestyle habits and history of diseases, and 88% answered similar forms again in 2014 and/or 2020. The 1,867 participants from Tromsø were also over 65 years old when they took part in the sixth edition of The Tromsø Study in 2007–2008, and just over half of them participated again in Tromsø 7 eight years later.

Almost 30% of the Birkebeiner athletes stated that they had atrial fibrillation, compared to just under 20% of the men from Tromsø. After taking into account that the athletes on average had far fewer risk factors for lifestyle diseases, lower BMI, higher level of education and healthier smoking and drinking habits, the risk of atrial fibrillation was increased by almost 90% compared to the Tromsø men. This difference is probably somewhat smaller in reality, as there was a higher proportion of athletes than general men who answered the follow-up questionnaires.

Regarding stroke, the incidence was 5% among athletes and 10% among the men from Tromsø. Athletes with atrial fibrillation also had a lower risk of stroke than non-athletes without atrial fibrillation. Overall, the results suggest that exercise-related atrial fibrillation entails a lower risk of stroke than atrial fibrillation caused by traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

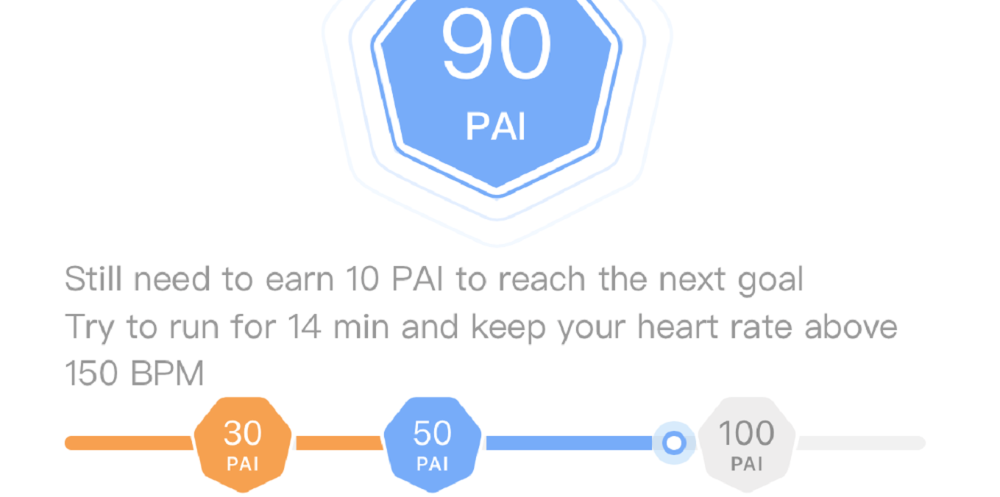

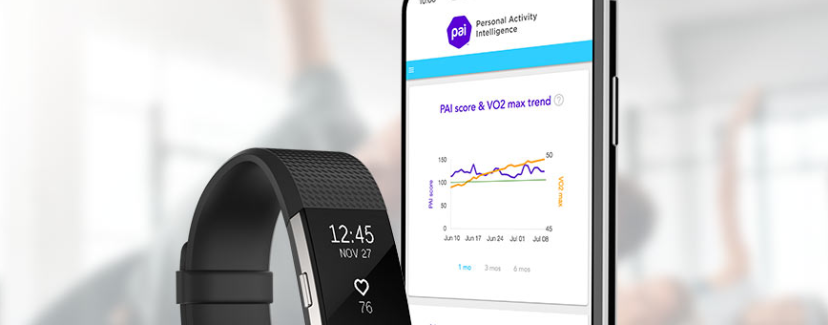

Older Chinese men and women who achieve a physical activity level of 100 PAI or higher have lower risk of a future heart attack than less active Chinese of the same age. The risk of dying from a heart attack or angina pectoris is also reduced for those who achieve 100 PAI, and this also applies to the middle-aged. The association between PAI and health risk apparently cannot be explained by other differences between active and inactive people, as the analyzes are adjusted for a number of such differences.

The study uses health information from close to 450,000 healthy men and women from ten different regions in China. Between 2004 and 2008, they reported their exercise habits and had a number of other health variables measured, such as blood pressure, BMI and blood sugar. 1,808 of the participants had a heart attack by 2015, while 3,050 died of a heart attack or angina. For people over 60 who achieved at least 100 weekly PAI, both the risk of having and dying from a heart attack was reduced by 16%. Also, among people with high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity, 100 PAI was linked to a lower risk of dying from a heart attack or angina.

Two specific changes in cardiac gene expression after high-intensity interval training might correct some of the damage that occurs in the heart when smoking. In a previous study, we showed that mice exposed to cigarette smoke had impaired heart function, but that six weeks of interval training almost reversed these impairments. We have now looked for genetic mechanisms that can explain these exercise effects.

It turned out that the expression of several genes in both the left and right heart chambers was different in the mice that had exercised, compared to the mice that were only exposed to smoking without exercise. Further investigations showed that two of the gene markers in the left ventricle - Agt and Retnla - are probably regulated by exercise in mice exposed to cigarette smoking. Smoking can damage DNA directly and also affect which RNA copies are made from the DNA. Similarly, exercise can change the expression of important genes. Based on the findings, we speculate that exercise-triggered changes in the Agt and Retnla genes may lead to better heart function and physical capacity in mice exposed to cigarette smoke.

The gene COX7A2L appears to be an important gene for physical capacity. Among other things, the gene affects the formation of important protein complexes in the mitochondria, which are the power plants of our cells. In the long term, the findings could potentially lead to new forms of treatment for lifestyle diseases, for example by changing the properties of this fitness gene in people who have a less favorable variant.

In the study, we used data from the HUNT3 Fitness study to confirm that the COX7A2 gene may be important for maximum oxygen uptake in humans. People with a genetic variant that gives increased levels of the RNA strand COX7A2L in skeletal muscle have higher maximum oxygen uptake than those who do not have this genetic variant. In addition, the study reveals, using data from other population studies, that the same favorable genetic variant can not only provide increased fitness, but also reduce body fat and body weight.

The study, which is a collaboration between researchers in Switzerland, Finland, Spain and CERG, shows that the composition of the COX7A2L gene is decisive for how many stable RNA copies the gene produces, especially in skeletal muscle cells. Ten letters in a specific part of the gene turned out to be the most important, Muscle fibers that have the "correct" letter composition in both pairs of this gene get increased levels of the RNA strand COX7A2L when the muscle cells are exposed to metabolic stress, such as exercise.

The energy that enables our muscles to move is produced in the mitochondria of muscle cells. The vast majority of energy production is dependent on oxygen, and takes place in the form of cellular respiration in four protein complexes inside the mitochondria. The protein complexes cooperate with each other in so-called supercomplexes, and mitochondria with well-functioning supercomplexes can thus play a role for oxygen uptake. The study shows that the COX7A2L gene plays an important role for these supercomplexes: Muscle fibers with the favorable genetic variant, which gives increased COX7A2L levels, also have more supercomplexes and an increased potential for cellular respiration in the mitochondria.

Finally, the study tested the effect of the fitness gene in a species of mice who are normally born without the Cox7a21 gene. Mice from the same species that were nevertheless bred to have this gene, had both increased maximum oxygen uptake, more muscle mass and increased energy consumption during physical activity. Furthermore, the results showed that exercise led to increased RNA levels of Cox7a2l in these mice, and that the exercise also produced more potent supercomplexes in the mitochondria.

Molecular changes in skeletal muscle may contribute to increased maximal oxygen uptake in patients with diastolic heart failure after a period of 4x4 interval training. This group of patients has hearts with normal pumping capacity, but which nevertheless beat weakly because they are unable to fill well with blood between each beat. Exercise seems to have a limited effect on the filling of the heart in these patients, and changes in the muscles can thus be directly decisive for achieving better fitness.

In a sub-study of the OptimEx study, we extracted muscle samples from some of the participants before starting, after three months of supervised exercise, and after a further nine months where they mostly were told to exercise on their own. We analyzed the gene expression of several proteins linked to muscle wasting and the activity of enzymes that are important for the metabolism in the muscle cells. Many patients with heart failure have a dysfunctional metabolism that can lead to reduced insulin sensitivity and muscle wasting. We also measured the quantity and function of satellite cells in the muscles. These are stem cells located outside the muscle fibres, but which after an exercise period can fuse with the muscle fibers and make them grow.

Both training with moderate intensity and interval training with high intensity gave the participants better fitness during the first three months, compared to the control group that did not participate in organized training. Moderate training only led to small molecular changes in the muscles. On the other hand, the high-intensity interval training influenced the metabolism in a favorable direction and also led to more satellite cells with better function. After twelve months, however, all the improvements had disappeared, which can probably be explained by the fact that fewer participants continued to follow the exercise plan after the face-to-face supervision ended.

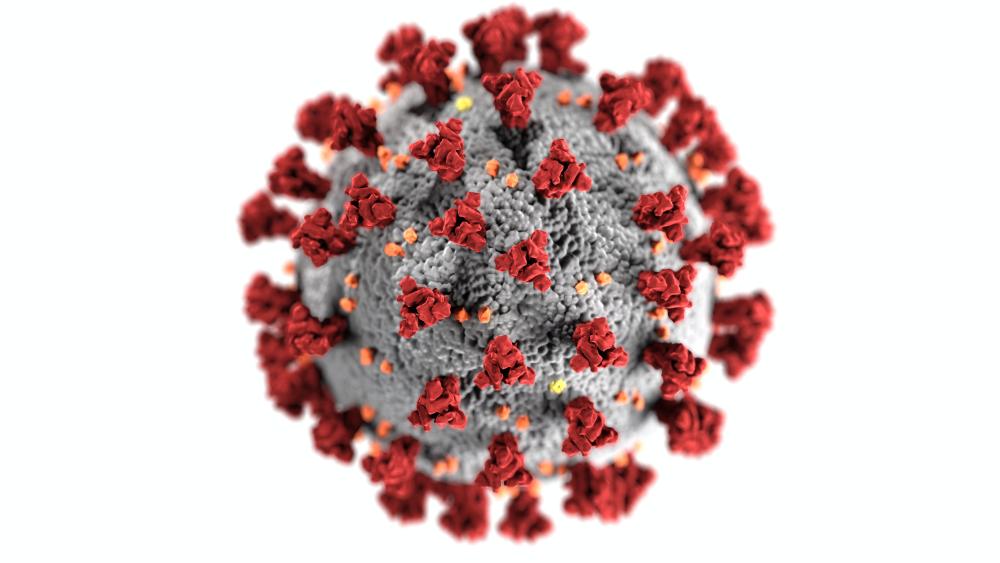

Most people who have been hospitalized with covid-19 have normal cardiorespiratory fitness one year later. The majority also achieved a higher maximum oxygen uptake than they had three months after admission. Nevertheless, almost a quarter still have poorer fitness than is expected for their age, and their fitness is lower than that of otherwise similar people without a history of covid-19.

In the study, we measured the fitness of 210 men and women who had been admitted to hospital with severe coronavirus disease during the first months after the pandemic arrived in Norway. We then compared with reference values for maximum oxygen uptake among Norwegians. After three months, 34% of corona patients had at least 20% worse fitness than most of their peers, while this proportion had dropped to 23% after a year.

We have also investigated whether the fitness of the covid patients differs from the fitness of others with the same sex, age, BMI, blood pressure and comorbidities. In these analyses, we have compared with selected participants from the HUNT4 Fitness Project, which was carried out in the years before the covid-19 pandemic. It turned out that the covid-19 patients had, on average, lower cardiorepiratory fitness than the HUNT participants.

The study, which was carried out in collaboration with six Norwegian hospitals, also indicates that physical inactivity is the most important reason why oxygen uptake is still impaired in some people 12 months after severe coronavirus disease. Limitations of the airways were rarely the cause, while the heart and circulation limited fitness in some of the patients.

Exercise has the same effect for patients with heart failure, regardless of whether the disease has ischemic or non-ischemic origin. Myocardial infarction is the most common cause of ischemic heart failure, while long-term high blood pressure and valve disease are among the most common causes of non-ischemic heart failure, where the failing pumping function of the heart is not due to a lack of oxygen.

In the SMARTEX-HF study, over 200 patients from nine research centers in Europe were randomly drawn to three groups. The participants were either followed up with supervised high- or moderate-intensity exercise for 12 weeks, or were given advice to exercise on their own. For the following nine months, all the participants exercised by themselves.

In this substudy, we compared participants from all three groups based on whether they had heart failure of ischemic or non-ischemic ethiology. Neither three nor 12 months of exercise follow-up had a different effect on the heart's structure or pump function, nor did physical fitness change differently in the two patient groups.

Calanus oil has no effect on maximum oxygen uptake

Healthy men and women do not improve their cardiorespiratory fitness by taking supplements with Calanus oil, which is extracted from the copepod calanus finmarchicus and is rich in omega-3 fatty acids. Previous animal studies gave us a hypothesis that this oil could have an effect on the maximum oxygen uptake. But after half a year of daily supplementation, fitness had not increased in the participants who received Calanus oil, compared to those who received placebo. Both at the start of the study and after six months, the average fitness number in both groups was approximately 50 ml/kg/min.

The participants were randomly drawn to receive a supplement with 2 g of Calanus oil every day, or an equivalent amount of placebo. Neither the participants themselves nor we who tested them knew which oil they received. We did not give them specific instructions about physical activity. 58 people between the ages of 30 and 60 completed the six-month study, and we tested their fitness both before, three months into and immediately after the intervention.

People who maintained an activity level of 100 PAI over a ten-year period – and those who increased from below to at least 100 PAI during the period – had a significantly lower risk of developing dementia over the next 25 years, compared to those who were less physically active. The risk of dying from or with dementia was also reduced for those who exercised enough to achieve 100 PAI. On average, participants with at least 100 PAI lived almost three years longer without dementia than those who were less active.

PAI - Personal Activity Intelligence - is a unique standard for measuring physical activity, developed by us at CERG. We obtained the results for the new study by analyzing data on almost 30,000 women and men who were healthy when they participated in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study in both the mid-1980s and 1990s. By using the Norwegian Cause of Death Registry and a local dementia register for the hospitals in Nord-Trøndelag, we found that just over 1,000 of the participants died of dementia by May 2020, while approximately 2,000 received a dementia diagnosis before February 2021.

The PAI score of the participants was calculated based on how active they reported to be when attending the two health surveys. Those who had a PAI of at least 100 in both the 1980s and 90s had a 38% lower risk of dying from or with dementia, compared to those who were physically inactive at both times. The risk of developing dementia was reduced by 25%. This reduction in risk applied after we had taken into account other differences between the active and inactive participants, for example that the inactive on average had higher blood pressure, smoked and weighed more, had lower education and more often lived alone.

We also saw an almost similar reduction in dementia risk among participants who were not sufficiently active to reach 100 PAI in the 80s, but who had increased to over 100 PAI by the mid-90s. In these participants, the reductions were 26% for dementia-related death and 17% for new-onset dementia, when compared to those who had less than 100 PAI at both measurement times.

In addition, we made separate analyzes for those who had high blood pressure, smoked or were overweight when they took part in the survey in the 1980s. In all these groups, we found that those who maintained their PAI score above 100 or increased from below to above 100 PAI during a ten-year period had a lower risk of developing dementia or dying from dementia during the follow-up period. Achieving 100 PAI was also more closely linked to dementia risk than meeting the health authorities' minimum recommendations for physical activity.

Older adults with poor cardiorespiratory fitness seem to be able to reduce the use of medication for anxiety, depression and sleep problems by improving their fitness. For those who already have a high maximum oxygen uptake, it seems less appropriate to further increase fitness.

The results are based on data on drug use and fitness among over 1,500 participants in the Generation 100 study. We measured the fitness of all the 70–77-year-old participants four times over five years, and obtained information on the use of medicines from the Norwegian Prescription Database throughout the entire period.

We found the highest use of medication for mental disorders among the least fit participants. Thereafter, the use of such drugs was gradually reduced with better fitness, up to a fitness number of 40 ml/kg/min. For the small number of participants who had even better cardiorespiratory fitness than this, drug use increased somewhat again.

The results were similar when we analyzed the use of antidepressants separately. On the other hand, we found no definite connection between cardiorespiratory fitness and the use of sleeping pills or anti-anxiety drugs, respectively.

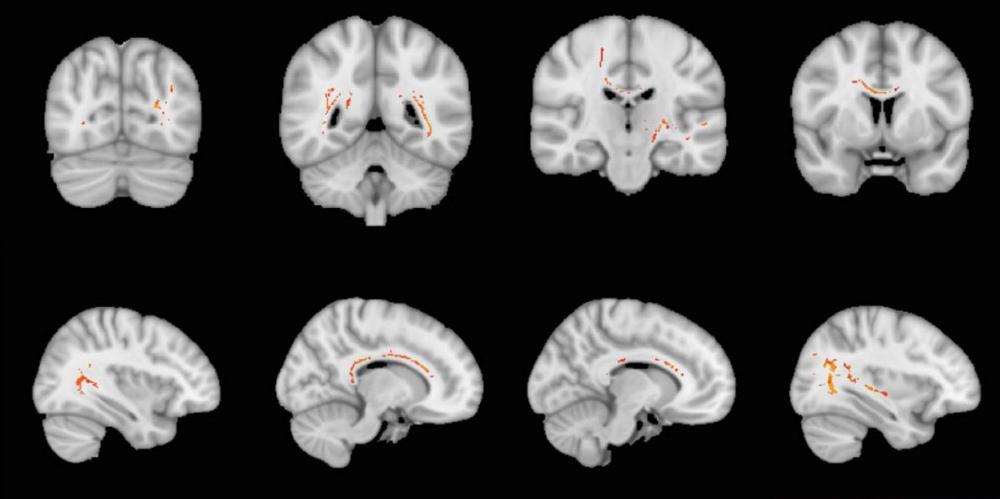

The wiring network in the brain was not better preserved in the Generation 100 groups that were offered organized exercise, compared with the participants who were advised to exercise on their own. Nevertheless, the results suggest that high fitness and high-intensity training are beneficial for maintaining better structure in this network.

Good signaling in the brain depends on intact nerve fibers and a thick layer of myelin that insulates these fibers. Together, nerve fibers and myelin form the white matter of the brain. In this study, we used MRI to examine the structural organization of white matter in 105 of the 70-77 year old participants in the Generation 100 project. The measurements were made at start-up and after one, three and five years of exercise follow-up, respectively.

Myelin ensures that molecules move along the nerve fibers instead of diffusing away from the fibers. A high degree of myelination therefore indicates good conduction capacity of nerve signals in the brain. Our results show that elderly people with high exercise capacity - in all three groups - had both a greater degree of myelinated nerve fibers and of molecules that moved along the nerve fibers. However, this correlation was strongest at start-up and after one year, and decreased after that.

The study also found a link between higher self-reported exercise intensity and better structure of the white matter of the brain. Here, too, the association was only present at the beginning of the study period. The results may be an indication that high-intensity training and high fitness protect against damage to the wiring in the brain in the elderly. At the same time, it may seem that this effect diminishes as one approaches 80 years.

In general, the findings agree well with other results on exercise and brain health from the Generation 100 project (see here, here, here, here and here).

High-intensity training leads to increased HDL-mediated nitric oxide production in the blood vessel wall of patients with heart failure with preserved pump function. Nitric oxide is essential for the ability of the blood vessels to dilate, an ability that is severely impaired in this disease. HDL particles in the blood - often referred to as the good cholesterol - can stimulate increased production of nitric oxide by binding to a specific receptor in the blood vessel wall. It is this property of the HDL particles that is enhanced by regular 4x4 interval training in heart failure patients, whereas the total levels of HDL in the blood are unchanged.

The HDL particles also increased their antioxidant capacity following regular high-intensity exercise. In line with this, it turned out that the interval training reduced the levels of an important marker for oxidative stress in the blood of the participants. This can be important in terms of reducing the degree of inflammation in the blood vessel wall and the risk of new cardiovascular events.

In diastolic heart failure, the heart is large and stiff, and the heart chambers have low ability to fill with blood. In the study, which includes 34 of the participants from the international OptimEx trial we have led, the patients were randomly assigned to 4x4 interval training, training with moderate intensity or to a control group that did not receive exercise follow-up. Before, during and after the exercise period, we took blood samples, isolated HDL particles from these samples, and performed experiments to see if the exercise changed the HDL particles' ability to initiate nitric oxide production.

During the three months of organized training follow-up, this ability only improved in the participants in the 4x4 group. However, the improvements were lost nine months later, after a period in which participants were encouraged to exercise on their own, but trained significantly less than they did during the first three months.

In people with heart failure, physical capacity is lower if kidney function is also impaired. This combination is called cardiorenal syndrome, and patients with this condition might also have less effect of endurance training than heart failure patients with normal kidney function.

Among 61 people with heart failure who participated in our study, 40 had reduced kidney function. These had on average a maximum oxygen uptake which was 3.5 ml/kg/min lower than the 21 who had normal kidney function. In addition, they walked almost 100 meters shorter on a 6-minute walking test. Even after adjusting for other factors that were different in the two groups, the difference in fitness and walking capacity was statistically significant.

All participants in the study first attended a two-day course called "Living with heart failure", where they among other things received advice on physical activity and exercise. Thereafter, half of the participants were randomly selected to be followed up with digital exercise sessions two days each week for the next three months. The exercise included high-intensity intervals, and each session lasted one hour.

After the three months, the participants with cardiorenal syndrome who did not receive exercise follow-up had reduced their maximum oxygen uptake compared to when the study started. Further, the cardiorenal patients in the exercise group did not improve their fitness. On the other hand, we saw a significant improvement in fitness among the participants with normal kidney function in the exercise group.

Both among people with type 2 diabetes and healthy people, we saw immediate impairments in heart function right after a session of 4x4 interval training. The impairments were mostly equal in both groups, suggesting that intensive exercise does not stress the heart more in people with diabetes. We know that regular exercise strengthens the heart, and usually the impairments that occur in the acute phase are transient, but we did not specifically examine that in this study.

The relatively small pilot study includes seven people with diabetes and seven otherwise similar people who did not have diabetes. They performed a 4x4-minute high-intensity interval session, directly followed by an exhausting test of maximum oxygen uptake. The hearts of all participants were examined with ultrasound just before the training session and 30 minutes after the session. The only thing that changed differently in the two groups was the thickness of the septum between the left and right ventricles at the point where the heart was maximally filled with blood. This wall increased in thickness in healthy people after the training session, which may indicate more fluid accumulation than in those who had diabetes.

We also took blood samples to see if the intensive exercise affected the blood sugar and the levels of troponin T – a marker of heart damage – differently in diabetes. However, there was nothing to indicate such a difference. Furthermore, the participants wore equipment that measured ECG for a whole day before and after the training session. Those with diabetes had far more arrhythmias in the form of extra heart beats than the healthy participants. This applied both before and after the training session, and an acute bout of exercise did not affect the number of extra beats the following day in any of the groups.

Increased fitness is linked to reduction of dangerous plaques for heart patients

Both heart patients who performed high-intensity intervals twice weekly, and patients who did not receive exercise follow-up, had more stable, less high-fat plaques in the heart's blood vessels after six months. The participants who increased their maximum oxygen uptake during the period achieved a more favorable plaque composition than those who had not increased their fitness. However, organized interval training was in itself no more effective than standard follow-up.

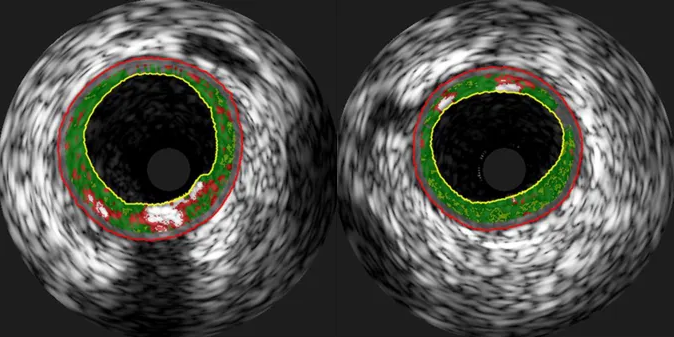

We used near-infrared spectroscopy to obtain very advanced images from inside the coronary arteries of the patients, and examined how the lipid content of the plaques changed over time. A high fat content in the core of the plaques makes them more vulnerable, and plaques that rupture can lead to heart attacks. The findings may indicate that increased fitness by exercise reduces the amount of this dangerous fat in the blood vessels of the heart.

All 60 participants in the study had recently been treated for coronary artery disease. Half were randomly drawn to join the exercise group, which attended supervised interval training with the 4x4 method two days a week for six months. The control group received regular exercise advice without an offer of direct follow-up. As more than half of the participants in the control group improved their cardiorespiratory fitness during the period, we suspect that a good number of them nevertheless increased the amount of exercise after joining the study.

Although we did not find any difference in plaque content in the two groups after six months, both groups had less high-fat plaques than at baseline. Moreover, both groups had increased the levels of the good HDL cholesterol. The interval training also led to increased fitness compared to the control group, as well as reduced body weight and waist circumference.

We have uncovered two new genetic variants that appear to be important for the VO2 max level in women. Based on our own fitness measurements of over 4,500 Norwegians, we found 38 genetic variants that were linked to high or low maximum oxygen uptake. When we looked at the same variants in blood samples from 60,000 fitness-tested Britons, we could confirm that two of them were decisive for the fitness level - at least in women.

The analysis is a so-called genome-wide association study, where we have examined the entire genetic material of participants in the HUNT3 Fitness study. Thus, we have been able to analyze 14 million genetic variants in these participants to see if they are linked to their fitness level. In the population as a whole, only two of these variants were significantly associated with fitness. However, when we analyzed women and men separately, we found 35 potential fitness genes in women and two in men.

Two of the gene variants that were important for VO2 max in Norwegian women were also significantly related to fitness in the British population. One of the genetic variant is located in a gene that is important for heart function and development of cardiovascular disease. Poor fitness is closely linked to an increased risk of lifestyle diseases, and part of the explanation can probably be found in our genes.

Most studies that have looked for fitness genes in the past have either not measured fitness with a maximum test on a treadmill with direct O2 measurements, or had few participants. Thus, this is the first large study that can use a sufficiently strict level of statistical certainty to uncover genes that are most likely directly linked to fitness. In addition, the study has revealed a number of candidate genes, which may have an impact on fitness but must be investigated further in other studies.

The Generation 100 study showed no effect of organized exercise follow-up on avoiding age-related changes in the structure of different parts of the brain. On the other hand, the participants who started the study with high aerobic capacity had better preserved structural complexity of cerebral gray matter - and specifically in the temporal lobe - compared with those who were less fit.

Better maintenance of fitness throughout the five years of the study was also associated with better preserved structure in the temporal lobe. This area of the brain is sensitive to physiological aging and the development of Alzheimer's disease.

In Generation 100, three groups of older women and men exercised differently, with two of the groups being offered organized exercise twice weekly. This substudy includes the 105 participants who underwent MRI scans of the brain before and during the study. A new method was used to assess structural complexity more accurately in different parts of the brain.

After five years, the measurements of structural complexity showed equal reductions in all three exercise groups. But a high maximum oxygen uptake was linked to better preserved complexity in parts of the cerebrum. The level of fitness had, however, no effect on the thickness of the cerebral cortex.

The results are largely reminiscent of other recently published findings on exercise and brain health based on the Generation 100 study. The general conclusion seems to be that high age-related fitness can be a key to maintaining important brain functions and avoiding wasting of brain tissue for the elderly.

The higher fitness level you get with our popular Fitness Calculator, the lower is the risk of having to undergo surgery to open narrow blood vessels in the heart. And when fitness is good, the probability of a long life is higher for those who have had heart surgery.

The study is based on over 45,000 Norwegians who participated in the second wave of the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study in the mid-1990s. None of them had previous heart disease. We calculated the fitness of everyone with the formula from the Fitness Calculator.

By the end of 2017, 672 of the participants had went through heart surgery due to a heart attack or angina. The risk was 11% reduced for each increase of 3.5 fitness numbers, which is also called 1 MET. In addition, people who reported being very physically active had a 26% lower risk than the least active.

466 of the 672 who had heart surgery survived the entire follow-up period. The probabillty of survival was 15% higher for each 1 MET increase in fitness level. Among those who had heart surgery, the fifth with the highest fitness levels in the 1990s had less than half the risk of premature death, compared with those with the lowest fitness.

We have found four micro-RNA molecules that change levels after a period of exercise, and which are also associated with reduced plaque burden in the coronary arteries of heart patients. The results come from a study in which 31 patients either trained intensive intervals or with moderate intensity three days a week after they had opened narrow blood vessels in the heart. We examined their vessels with intravascular ultrasound both before and after the exercise period.

Micro-RNAs are tiny particles that regulate the activity of our genes. Many micro-RNA molecules are involved in various stages of the atherosclerosis process that clog blood vessels and lead to cardiovascular disease. In this study, we pre-defined 13 micro-RNA molecules that we examined further, based on results from previous studies.

After three months of training, the levels of micro-RNA-146a-5p had increased, while the levels of micro-RNA-15a-5p, 93-5p and 451a had decreased. All of these changes were also linked to a reduction in the total amount of plaque in the blood vessels of the patients. The study can not say anything about causation, but we can speculate that exercise leads to changes in micro-RNA that are beneficial in reducing coronary artery plaques in heart patients.

In addition, we found that the levels of six micro-RNA molecules were linked to a larger necrotic core. This plaque core consists of inflammatory cells and fat, and plaques with a lot of fat are more vulnerable to rupture that leads to heart attacks. However, changes in this necrotic core after an exercise period were not related to how micro-RNA levels changed during the same period.

The pumping function of the heart's right ventricle is somewhat reduced in people who have been hospitalized with severe covid-19 disease a few months ago, compared to otherwise similar people from the general population. The right ventricle pumps blood out into the pulmonary circulation, and the function was worst among the patients who had been admitted to the intensive care unit. More of the corona patients also had impaired filling of blood between each heart beat.

The study, which is led by our researcher Charlotte Björk Ingul in collaboration with researchers from five Norwegian hospitals, includes a total of 204 people who were admitted with covid-19 between February and June 2020. Each participant was matched with one person who was examined with cardiac ultrasound as part of the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Thus, the two groups were similar in terms of age, gender, BMI, blood pressure, previous heart and lung diseases, and diabetes. The corona patients also wore equipment that measured ECGs for 24 hours. 27% of them had cardiac arrhythmias three months after admission, mainly premature ventricular contractions and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. No one developed atrial fibrillation after their covid-19 disease.

The lipoprotein profile of healthy people with low maximum oxygen uptake is similar to the lipoprotein profile of people with insulin resistance. We know that persons with low cardiorespiratory fitness have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and an unfavorable lipoprotein profile appears to be a probable part of the explanation. The results are based on data from the fitness testing of 211 healthy, middle-aged Norwegians who participated in the HUNT3 Fitness project. Half had high fitness, while the other half had low fitness, despite the fact that both groups were the same age and reported the same level of physical activity.

In the study, we used advanced nuclear MRI technology to study the levels of fats in 99 subgroups of the lipoproteins HDL, LDL, VLDL and IDL. Especially in the largest of the VLDL particles, we found increased levels of lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides in those with low fitness. This group also had 15% higher VLDL levels overall. In addition, they had higher fat content in small LDL and HDL particles. HDL particles are often referred to as "good cholesterol" because they can protect against atherosclerosis, but this probably only applies to large and medium-sized HDL particles. Small LDL particles can also play an important role in the formation of harmful plaques in blood vessels.

We found no beneficial effect of high fitness or long-term organized exercise on the development of white spots in the brain of older adults. These spots can be seen on MRI, and are common after the age of 50. The spots are scars in the wiring in the brain, and are associated with impaired gait function, cognitive impairment, depression and stroke. Neither in the participants who were offered organized interval training with high intensity, nor in those who could attend moderate training sessions, did the growth of these scars develop differently than in those who exercised on their own.

The study includes 105 of the participants in the Generation 100 study. Their brains were checked with MRI before, during and after the five-year exercise period. The extent of white spots increased in all three groups, especially during the last couple of years of the 5-year period. The other three studies we have published on brain health in the Generation 100 study show that high fitness protects against cognitive impairments. However, we found no association between fitness and the development of white spots. Nor did those who improved their fitness during the study have slower development of white spots in the brain than the rest of the participants.

Blood plasma from exercised mice gives older, untrained mice better brain health. Recently, we initiated the ExPlas study, where we investigate whether people who have already developed Alzheimer's disease can benefit from plasma from fit, young donors. In a new review article, we address all previous research on exercise, fitness and Alzheimer's disease, and also look at the mechanisms that may explain why exercise that increases fitness can be an effective medicine to prevent and treat dementia.