Writing Effective Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

Writing Effective Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

Written by SFU Excited, Cluster 1, Clusterleader Rune Hjelsvold.

An outcome is a consequence of something: the result of an action or situation. There can be

numerous possible outcomes from any particular event that can be intended or unintended,

desirable or undesirable. A learning outcome can therefore be thought of as a result of learning; an

intended learning outcome (ILO) is a deliberate, desirable and predicted outcome of learning. To

validate whether that ILO has been achieved, you must be able to observe or measure it. ILOs focus

on the product rather than the process: what has been achieved rather than what has been taught.

In the context of educational systems that offer certification of successful completion of a learning

programme, an ILO statement (or list of statements) describes what end-product(s) are expected

from somebody participating in that programme. Therefore, an ILO, in the context of merited

education, is both a statement of intent and a success criterion. For success to be endorsed, and a

certificate awarded, then the participant of the learning programme must be able to evidence that

they have achieved the success criteria.

For the student, having well-formulated ILO statements help direct their learning towards a clear

objective. It also gives the student a clear indication of how to evidence that they have met the

success criteria. For the teacher, having well-formulated ILO statements provide a useful starting

point for planning teaching and assessment activities. Writing effective ILOs allows the teacher to

align the objectives of a course with the teaching methods and the assessment of learning, thus

confirming whether the outcome is as intended.

Competence based ILOs.

Competence based ILOs.

The word competent is an adjective describing having the skills or knowledge to do something well enough to meet a certain standard or being able to function for a particular purpose. Competence (or competency) is a noun identifying the state of being able: having the generic capability that is a necessary requirement to perform, or the set of characteristics which enable performance. Competence is therefore performative: demonstrated in a contextual setting by carrying out specific goal-oriented tasks to a required standard.

Using a competence-based approach to writing ILOs naturally leads to considering the observable or measurable result of learning as a demonstrable action. The competence-based approach also recognises a paradigm shift from teacher-centred to student-centred higher education: it overtly recognises that the student is responsible for demonstrating his/her own learning and must evidence their attainment of key competencies before being judged to have successfully completed a programme of learning. A successful student will be able to perform a task, to a required standard, which evidences that they have the skills or knowledge needed to perform that task.

The Language of ILOs

The Language of ILOs

When writing ILOs, it is important that statements are specific and well defined. They should explain the specific actions, in clear and concise terms, that would evidence that the student has satisfied the ILO.

It is important that outcomes are stated in the future tense, in terms of what students should be able to do as a result of learning. ILOs should also include performative actions that are observable or measurable. For example, ILOs such as “Students will develop their understanding of…” describes the process rather than the outcome, and is a latent term that would be difficult to quantify.

Compounding two or more outcomes into one statement is something that should be avoided. For example, the outcome “Students should be able to interpret and analyse data to produce meaningful conclusions and recommendations within a written report.” is a bundled set of outcomes that separately address different goals: one about analysing data and another about communicating results.

Effective ILOs should begin with the phrase “Upon successful completion of the course, the student should be able to…” and then follow with an action verb, an object and some context.

The components of a learning outcome should be as follows:

Example:

On successful completion of the course, students should be able to…

Examples:

The following are examples of ineffective ILOs, the reason they are ineffective and a suggestion for improvement:

“Understand the amendments of the United States Constitution.”

This is a little vague and difficult to observe or measure directly. What about the amendments do you want them to understand, and how will you know if, and to what extent, the student understands them? A suggestion for improvement might be: “Describe the ratification process of proposals made by the US congress to make amendments to the US constitution.” This is much more concise in how the student is expected to demonstrate their understanding of the ratification process of proposals for amendments. The student would need to understand the process in order to describe it.

“Read and review literature on global climate change.”

Reading demonstrates basic literacy and is probably not an intended learning outcome of this course. Reviewing literature on climate change is closer to the mark, however still fails to describe how that review will be presented as evidence of learning. A suggestion for improvement might be: “Write a review summarising published literature on global climate change.” This expresses the expected end-product more succinctly.

“Learn how to operate a fork-lift truck.”

This describes the process and not the expected result. It could be assumed that the people enrolling this course will do exactly this, but it lacks context. A suggestion for improvement might be: “Demonstrate safe operation of a fork-lift truck in an industrial workplace.” This states clearly that

the requirement is to be able to operate a fork-lift truck safely and gives the context of the training.

“Complete a quiz on dinosaurs.”

This describes the assessment task and not the learning outcome. What should the student know in order to be able to successfully complete the quiz? A suggestion for improvement might be: “Identify differences between different species of non-avian dinosaur found during the Triassic

period.” This statement gives information on the specific subject matter, and what the student should be able to do as a result of learning.

Domains of Learning

Domains of Learning

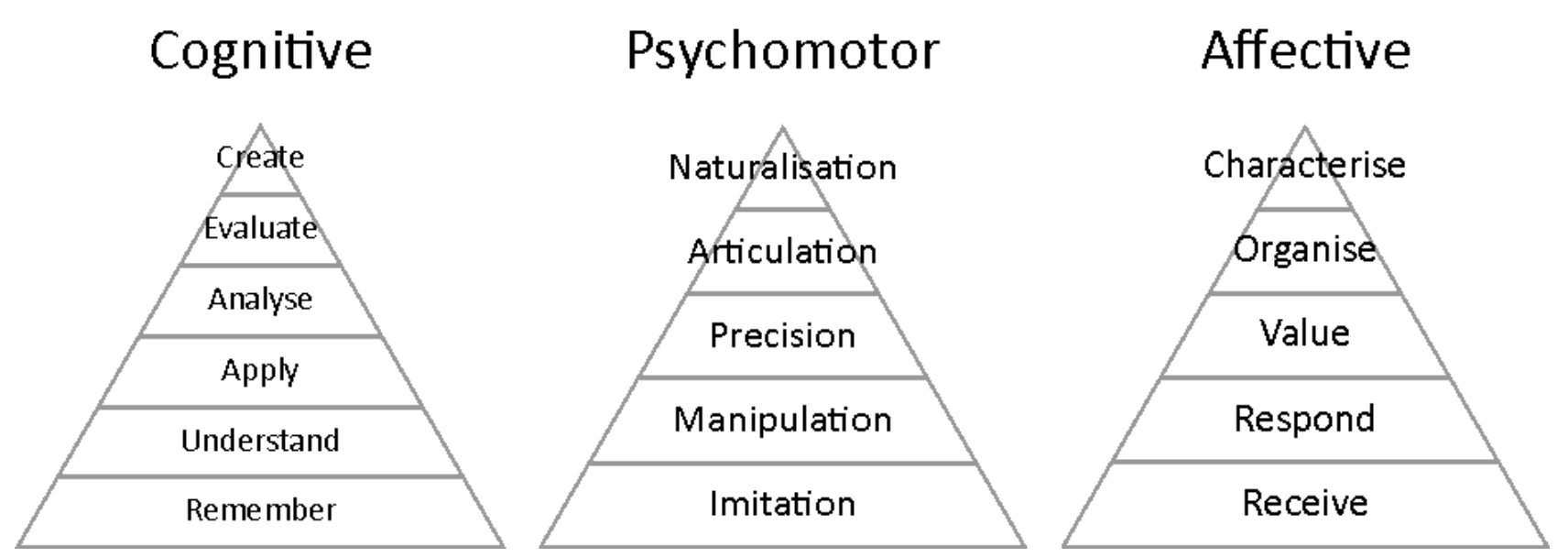

Between 1956-1972, three main domains of learning were identified and described:

- The CognitiveDomain,

- The Psychomotor Domain and

- The Affective Domain.

At the forefront of this was Benjamin S. Bloom, with contributions from a committee of college and university examiners in the publication

of "Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals" (1956).

The 1956 edition had the subordinate title of "Handbook I: Cognitive Domain". The intention was to promote higher forms of thinking in education, such as analysing and evaluating concepts, processes, procedures, and principles, rather than just remembering facts (rote learning). In their description of the cognitive domain, Bloom et al. presented a hierarchical model that showed a sequential and progressive categorisation of learning in the form of a taxonomy.

The three domains of learning, and accompanying taxonomies, have had several revisions by various educational psychologists over the

years, most notably the 2001 revision of the cognitive domain, and have become widespread as tools to support the design of educational, training, and learning processes. The taxonomies of learning are commonly used as a framework for considering the expected level and progression of

learning, and for reference when writing ILOs.

Cognitive (knowledge) – to think

In the original 1956 version of the taxonomy, commonly referred to Bloom’s taxonomy, the cognitive domain is broken into six levels of educational objectives: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The taxonomy was revised by Anderson and Krathwohl in 2001, with a more systematic rationale and improving the usability of it by using action words. In the revised version, levels five and six (synthesis and evaluation) were inverted. Another notable revision is the relaxation of the strict hierarchy: the 2001 taxonomy allows for some overlap of the categories. Debate continues as to the order of levels five and six, however much of this is dependent on interpretation of the category names. Anderson and Krathwohl define Evaluate as “Making judgements based on criteria and standards” and Create as “Putting elements together to form a novel, coherent whole or make an original product”.

To put it another way, you should learn to evaluate existing knowledge or products before adding new perspectives or creating new products. A literature review comes before a new research project; market research comes before a new product is designed. With this in mind, the Create category’s focus on innovation would align with the levels of education, whereby a Ph.D. requires new knowledge to be presented, and would justify the higher level of complexity.

Using the revised (2001) version of the cognitive domain, the following table describes the levels of learning in ascending order of Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyse, Evaluate and Create:

The taxonomies, and descriptions of their levels, can be used to select appropriate action verbs when developing ILOs. There are many resources available giving examples of verbs, the following table provides a few selected examples:

Bloom's original cognitive taxonomy described three categories of knowledge: factual, conceptual and procedural. In Anderson and Krathwohl’s revised version, they added another category of knowledge: metacognitive. Others (Clark & Lyons, 2004; Clark & Mayer, 2007) have since expanded on this. Put into an example matrix, it can be a useful aid for creating performance objectives:

Affective (attitude) – to feel

The Affective Domain was classified and described by Krathwohl, Bloom and Masia (1964) in Handbook II of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives and presents a taxonomy for developing attitudes, character and conscience – also expressed in various literature as interests, appreciations, values or emotional sets. The authors make a point of noting that structuring the affective domain was significantly more difficult than the cognitive domain. One reason for this was the lack of evaluation material: it was very seldom being explicitly assessed in education. This can perhaps be explained by the difficulty in quantifying affective learning, which rather relies on qualitative judgement or personal reflection. It was, however, deemed important to provide a classification for affective objectives.

Central to the affective domain is the concept of internalisation: whereby interacting with external stimuli progressively shapes the individual’s perspective of the world.

A description of the levels with selected examples of action verbs is presented below:

Psychomotor (skill) – to do

Bloom and his colleagues never published a third handbook to complete the expected triptych of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, presumably due to the difficulties they had structuring the second one for the affective domain and their dissatisfaction with the result. They had stated in their first handbook that there was very little done in secondary schools and colleges relating to motor skills and that they didn’t believe a classification would be useful at that time. The lack of evaluation material had been a struggle of the second handbook, so one would expect that they anticipated even less to support the third. In the 2001 revision, Anderson and Krathwohl declared that the original group always considered the framework a work in progress, neither finished nor final. Other educational psychologists have since taken on this work and presented taxonomies of this domain.

There are three commonly referenced taxonomies within the psychomotor domain:

- Dave (1970),

- Harrow (1972) and

- Simpson (1972)

These are also recognised in Krathwohl’s overview of the 2001 revision of the original taxonomy. The Simpson and Harrow psychomotor taxonomies are especially useful for describing the development of the relationship between cognition and physical movement from birth through to adulthood, or for developing skills within the performing arts and sports. The psychomotor taxonomy by Dave is perhaps more transferable across disciplines as there is less emphasis on movement, and rather describes progressive degrees of competence in performative actions.

A description of the levels, using Dave’s taxonomy (1970), with selected examples of action verbs is presented below:

Entry point and exit point

Entry point and exit point

One important thing to consider when using taxonomies to formulate ILOs is the entry and exit point of the student. What is their expected prior learning? To what level do you expect to take them? When considering these questions, you must think about not only the level of education you are working within, but also the scope of the learning experience you are writing the ILO for. For example, are you writing an ILO for a graduate learning outcome at Bachelor level, are you writing an ILO for a course within an undergraduate degree programme, or are you writing an ILO for an individual teaching session? Whatever the scope, the ILO(s) should describe the end goal of the learning experience; not a sequential and progressive list of stages that will get them to that end goal.

Education as a whole (levels 1-8)

Using the European Qualifications Framework for reference, and with the cognitive domain taxonomy as an example, we can map the whole educational system to the hierarchy of educational objectives. Using this as a tool is a useful way to think about graduate level learning outcomes at an institutional or study programme level. We get an idea of how far along the educational system the student is, what level of knowledge we can expect them to have on entry and what level we should be aiming towards. However, this is only useful if the subject matter is covered at all previous levels of education.

Using the Norwegian national curriculum as an example, the common core subjects throughout primary and secondary compulsory education are;

- Norwegian

- Mathematics

- Natural Science

- English

- Social Science

- Geography

- History

- Religion

- Ethics

- Physical Education.

If you were considering the entry point at further education in one of these subjects, you could therefore expect students to have a foundational knowledge. Once compulsory education ends, and students can choose their own path, then you might not be able to expect each student to have the same learning experiences. If you are considering the entry point for a student starting a Bachelor’s degree, then you must consider what they have studied during non-compulsory education. If you are recruiting students from other countries, that might have a different national education framework, then there might also be differences in the students’ level of knowledge in certain academic disciplines.

Academic disciplines broken down

An academic disciple (e.g., mathematics, engineering, fine art) is likely to closely represent the mapping of the taxonomic levels to the educational levels as above: you would expect that students have had some foundational education in each academic discipline throughout their general education. However, following general education, these academic disciples tend to separate into more specific subjects (e.g., computer science, animation, microbiology). New concepts, processes and skills are likely then introduced. With these new concepts, processes and skills comes a need to reconsider the educational objectives. Is this a new set of concepts, processes and skills that requires a new foundation of knowledge? If so, you might then need to think of the entry point being a taxonomic level-zero and begin with addressing the basics of recognising and remembering facts, terms and concepts and progressing to understanding, applying and synthesising them.

The same might be true of specific skills within a subject. Using animation as an example, character design, storyboarding and compositing are all quite separate skills that require different competencies. The conceptual knowledge of these skills may have been introduced during a general animation foundation course but might be taught as specialisms in a higher educational level programme. The entry point then might be different for the specialist course than the entry point to the study programme.

What might result from all this, is that you have nested taxonomies that describe the academic discipline, the subject area and the individual topics within those subjects. These nested taxonomies might also necessitate the introduction of different learning domains at different levels of study (for example a new psychomotor skill within a practical aspect of an academic discipline):

In summary, whether you are working at governmental, institutional, faculty or department level – designing a national curriculum, a study programme, a course or an individual teaching session – you need to consider the expected entry point and targeted exit point of the students that are going to be educated. Knowing this will help you to construct ILOs that are appropriate and help both you and the students understand the expectations of one another.

Assessment

Assessment

It is easy to become so immersed in the job of teaching that we lose sight of the exact purpose of a particular piece of assessment. If we do not isolate the purpose of an assessment activity, we risk failing to assess the ILOs. The implications of this are that it doesn’t give the students the opportunity to demonstrate their learning, it creates confusion for the students and the assessment becomes a waste of time.

Writing effective ILOs helps you identify the best assessment method to determine that the learning outcome has been satisfactorily achieved. By designing your assessment methods based on the intended learning outcome, you give purpose to the assessment. The action verb used in an effective learning outcome is usually a good indicator for the assessment method.

Constructive Alignment

Constructive Alignment

Constructive alignment starts with the notion that the learner constructs his or her own learning through relevant learning activities. The teacher's job is to create a learning environment that supports the learning activities appropriate to achieving the desired learning outcomes. The key is that all components in the teaching system – the curriculum and its intended learning outcomes, the teaching methods used, the assessment tasks – are aligned to each other. The learner finds it difficult to escape without learning appropriately!

Formative and Summative Assessment

Formative and Summative Assessment

There is an important distinction between assessment which is intended to help the student learn and assessment intended to identify how much has been learnt. Formative assessment is most useful part way through a course or module, and will involve giving the student feedback which they can use to improve their future performance. Summative assessment is the final evaluation of the students’ performance. Assessment should be seen as an intrinsic part of the learning process rather than something which is ‘tacked on’ at the end to attribute grades. It should therefore be seen as a vital part of the initial design of the course.

Using a constructive alignment matrix can help to map the intended learning outcomes with the assessment and teaching methods:

Conclusion

Conclusion

Writing effective learning outcomes is an important stage in the successful design and delivery of any educational activity. A well-formulated learning outcome gives you the structure to design your teaching and assessment activities and clearly articulates to your students what is expected of them. At the end of the educational activity, the students will be able to demonstrate what they have learnt, and you will be able to determine whether they have learnt what you intended them to.

Using taxonomies of educational objectives is a useful reference for determining the expected entry point of your students and also for planning how far through their learning journey you intend to take them. Whilst these are a useful tool, you should be conscious not to be governed by them: use them alongside your experience and academic judgment. The taxonomies, whilst presented as three separate learning domains, are not intended to represent a total disconnect between knowledge, skills and attitudes. Education should be treated holistically, and effective learning requires good interplay between knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Effective educational design begins with determining at what stage of learning your students are and to what stage of learning you intend to take them. Taxonomies of learning provide a reference for this, and help educators to articulate their intentions and expectations. Writing effective ILOs helps you to design teaching activities to transport learners from one stage to the next, and gives you assessment measures to know that they got there adequately.

Key questions when assessing the quality of intended learning outcomes (ILOs)

Key questions when assessing the quality of intended learning outcomes (ILOs)

Key questions when assessing the quality of intended learning outcomes (ILOs):

Atomistic questions

1. Does the ILO describe how subject knowledge, practical skills or general competencies will be exhibited (manifest rather than latent) by an individual upon successful completion of the educational activity?

2. Is the level of the ILO appropriate to the exit point of the educational activity to which it refers?

3. Can the ILO confidently be placed within a single learning domain (cognitive, psychomotor or affective)?

Holistic questions

1. Do the ILOs collectively and concisely describe the technical and non-technical graduate outcomes (refraining from listing implied foundation and intermediary outcomes)?

2. Are the general competencies transferable to other disciplines or professional contexts?

Background and motivation

This addendum to the key quality assessment functions gives a short introduction to the three learning domains that learning outcomes are related to. It further exemplifies how the questions may be used to detect quality issues in ILOs.

The three learning domains

Cognitive: In the original 1956 version of the taxonomy, commonly referred to Bloom’s taxonomy,the cognitive domain is broken into six levels of educational objectives: knowledge, comprehension,application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The taxonomy was revised by Anderson and Krathwohl in 2001, with notable changes to levels five and six (synthesis and evaluation). Anderson and Krathwohl define the revised level five as Evaluate (making judgements based on criteria and standards) and level six as Create (putting elements together to form a novel, coherent whole or make an original product).

Psychomotor: There are three commonly referenced taxonomies within the psychomotor domain:Dave (1970), Harrow (1972) and Simpson (1972). These are also recognised in Krathwohl’s overview of the 2001 revision of Bloom’s taxonomy. The Simpson and Harrow psychomotor taxonomies are especially useful for describing the development of the relationship between cognition and physical movement from birth through to adulthood, or for developing skills within the performing arts and sports. The psychomotor taxonomy by Dave is perhaps more transferable across disciplines as there is less emphasis on movement, and rather describes progressive degrees of competence in performative actions.

Affective: The Affective Domain was classified and described by Krathwohl, Bloom and Masia (1964)in Handbook II of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives and presents a taxonomy for developing attitudes, character and conscience – also expressed in various literature as interests, appreciations,values or emotional sets. Central to the affective domain is the concept of internalisation: whereby interacting with external stimuli progressively shapes the individual’s perspective of the world.Example quality assessment

Example programme: Computer Science - master's program (Master of Technology)

A student who has completed the program is expected to have achieved the following learning outcomes, defined in terms of knowledge, skills and general competence:

Knowledge: Broad mathematical-natural science, technological and data engineering basic knowledge as a basis for understanding methods, applications, professional renewal and restructuring.

• This ILO describes possessing a broad, basic knowledge as a basis for understanding. It does not describe how that knowledge will be exhibited. Possessing knowledge is a latent term that cannot readily be observed or measured.

• The areas of knowledge described as mathematical-natural science and technological are somewhat vague and perhaps need to be described within their own ILO.

• Understanding, as a graduate outcome, is somewhat below the study programme level of a master’s degree. At level 7, you would expect graduates to be capable of demonstrating a higher-level knowledge such as analysis and evaluation.

• Professional renewal is included in this ILO which is perhaps out of place. Understanding professional renewal, as suggested in this ILO, might be an awareness of continuous professional development (CPD) as a concept; however, it is anticipated that a preparedness to engage in CPD is the more likely intended outcome. This would be better mapped to the affective domain of learning and placed under general competence rather than subject knowledge.

Skills: Define, model and analyse complex engineering problems within computer technology, including choosing relevant models and methods, and carry out analyses, build and evaluate solutions independently and critically, in relation to both technical and non-technical factors.

• Defining a problem would be an expression of knowledge rather than a skill, as would choosing a relevant model and method.

• Carrying out an analysis (analysing something) would generally be considered to be within the cognitive domain; however, this ILO description suggests that computational modelling will be used which might require certain technical skills. The necessary technical skills should be described separately from a general description of analysis.

• Building a solution to a complex engineering problem would assumably require a thorough understanding of the problem, a validated methodology necessary for solving the problem and the technical skills to build the architecture of the solution. The knowledge components and skill components need to be separated out here.

• Evaluation of a solution can be done without having built it. It can therefore be considered as a standalone outcome. Evaluation, in the context described here, should likely be considered under the cognitive domain and be described as an expression of knowledge. Critique forms part of an evaluation and does not need to be additionally listed. As the learning outcomes here describe the graduate as an individual, the inclusion of the word “independently” is not necessary as it is implicit throughout.

• Evaluation would usually consider the whole. If there are specific “technical and non technical factors” that are important to include, then these should be clearly described.

• The levels of analysis and evaluation seem appropriate for a master’s degree graduate.Building a solution to a complex engineering problem might be venturing further into the generation of new knowledge. It perhaps needs to be considered whether this involves building an implementation of a known solution or actually solving a problem through a novel invention, and thereby whether it is an appropriate expectation for this level of study.

General competence: Understand the role of engineering and computer technology in a holistic societal perspective, have insight into ethical requirements and considerations for sustainable development, and be able to analyse ethical issues related to engineering work.

• “The role of engineering and computer technology” seems to be subject knowledge rather than general competence, and therefore misplaced. Of course, it is useful to consider these things from a social, as well as a technical, perspective, but this is still about understanding the subject area rather than describing a transferrable competence.

• Ethics and sustainable development could certainly be considered transferable, but what exactly are the competencies expected here? “Having insight” is a latent term that cannot readily be observed or measured.

• Ethics and sustainable development should be considered independently and described as two separate ILOs.

• Ethical requirements might also be separated from ethical issues. It might be fundamentally important, and a basic knowledge component, to recognise applicable ethical regulations. Considering ethical issues in terms of moral and social values might instead be considered within the affective domain and more of a general competence.

• Sustainable development needs elaborating on, and with a clearer outcome described. “Considerations for sustainable development” is another latent term that cannot readily be observed or measured.

- Follow us on social media

- Follow Excited on Instagram

- Follow Excited on X

- Follow Excited on Facebook